While there has long been a crusade from the powers that be to de-fang small publishers and independent songwriters as much as possible to prevent them from suing major companies like Spotify, the streaming platform’s new public status could shareholders a legal leg-up.

________________________

Guest post by Chris Castle of Music Technology Policy

The Digital Media Association is as obsessed with crushing the ability of independent songwriters and small publishers to sue companies like Spotify for copyright infringement as the industry negotiators are with presenting a new safe harbor for infringers like it was a fantastic give in the Music Modernization Act. But at least where Spotify is concerned, as a public company they may be begging for the very statutory damages they are so anxious to eliminate.

Spotify lawyers like Christopher Sprigman and his compadre Lawrence Lessig have been trying to get rid of statutory damages and bring back 1909-style copyright registration for years. (See also Pamela Samuelson and the list goes on.)

But now that the industry has acquiesced in both of those long cherished goals of the anti-copyright crowd, songwriters will have to look elsewhere to regain the kind of punch that they got with the statutory damages stick. Why? Because a benevolent and patriarchal government is taking that stick away from the little guy and giving it to the largest corporations in commercial history. (And recording artists and record companies–you’re next and you’ll know who to thank. See Transparency in Music Licensing and Ownership Act that is quietly adding co-sponsors.)

But you say, what could be a bigger stick than statutory damages? It might be shareholder derivative suits. And Sprigman’s benefactor Google is a great example of what that means.

MTP readers will recall that we have written before about Google’s “dual class shares” that created 10 for 1 supervoting stock that is owned only by insiders like Eric “Uncle Sugar” Schmidt, Larry Page and Sergey Brin. If you’ve ever watched the video of a Google shareholder meeting, you’ll have seen David Drummond (who has his own problems) reading out the news of how any shareholder motion that was not supported by the insiders was defeated–and massively defeated due to the supervoting stock. The only thing that’s remarkable is that the shareholders keep trying. Because while all shareholders are equal, at Google, some shareholders are more equal than others. Ten times more equal if they give you voting stock at all. Google shareholders give the right to be forgotten a whole new meaning.

That’s right–Google has what I call the “you break it, you bought it” class of stock that gives the insiders total control over all aspects of their corporation. If you’re not an insider, your role is to shut up and enjoy the ride. Don’t get me wrong–lots of people do.

But some don’t. Most recently, a Google shareholder tried to question the company’s top executives about their pre-#metoo opposition to the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act.

If you watch the video, you’ll get the idea. Google is comfortable with their opposition to stopping sex trafficking in favor of profitable safe harbors, so sit down, shut up and count your money. That should demonstrate two things: First, the Alphas are not interested in anything anyone else has to say although they will go through the motions to tolerate the poor Epsilons. Second, these policy positions and more importantly corporate actions are solely the responsibility of the insiders in the More Equal Than You system of corporate governance.

And guess what? Bloomberg reports that Silicon Valley mogul wanna be Daniel Ek mimicked the Google model with the supposedly egalitarian Spotify.

Chief Executive Officer Daniel Ek and Vice Chairman Martin Lorentzon own a class of stock that assures their hold on the company after the shares begin trading, said the people, who asked not to be identified because the terms aren’t public. Another class will be tradeable by investors.

That means public investors will be able to own part of the world’s largest paid music service in the next couple of months, but won’t have much say about its future. Years after going public, some of the biggest technology companies, including Google parent Alphabet Inc. and Facebook Inc., remain under the control of founders who hold shares with super-voting rights.

Company founders employ so-called dual-class structures to take advantage of the perks of being publicly traded without surrendering control. Such owners can make acquisitions that dilute their economic interest without loosing their grip.

Ek, who co-founded Spotify about a decade ago in Stockholm, has looked to such companies for direction. He invited Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg to his wedding and has publicly praised the leadership of Snap Inc., which gave its investors no voting rights in its initial public offering last March.

If the Google shareholder meetings are any guide, it’s not that investors won’t have much say, they won’t have any say at all. Unless they are sued by their stockholders in what is called a shareholder derivative suit. A shareholder suit is when a shareholder sues the corporation’s officers or board of directors for a cause of action against the corporation that isn’t being brought because it would require the board of directors to sue itself. These are often based on breach of fiduciary duty.

Case in point: Google’s sale of advertising promoting the sale and distribution of illegal drugs. Google signed a nonprosecution agreement with the Department of Justice, second cousin to a plea bargain, after a four year grand jury investigation, producing four million documents to the investigators and paying a $500,000,000 fine. Walking around money for Google, but nobody was fired and according to the U.S. Attorney bringing the case, the paper trail implicated Google’s senior management including Larry Page (which disclosure resulted in an apology to Google from the DOJ and the “muzzling” of the US Attorney,)

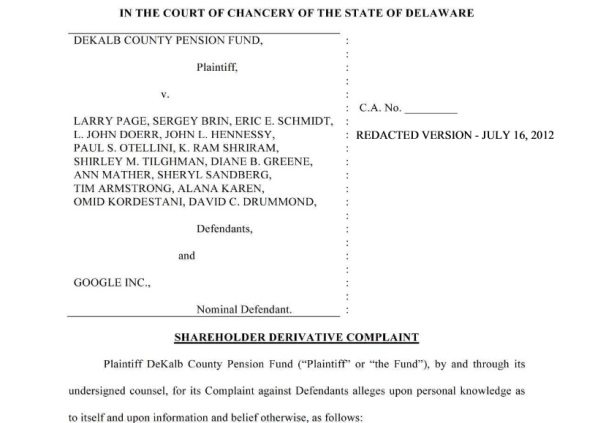

Shareholders were pissed and a pension fund brought a derivative case (read the complaint) against the Google board including Page, Brin, Schmidt, John Doerr and Sheryl Sandberg. (Yes, that Sheryl Sandberg.) This case resulted in a settlement that required Google to spend over $250,000,000.

So this is the kind of thing that stockholders bring themselves when they know that the government never will and there’s a case to be made. Shareholder suits are kind of like the “private attorney general” laws that used to be in the Copyright Act where the government avoided the burden of actually enforcing its laws itself and instead relied on the market to do so. How did they do this? By giving private actors a big stick like the statutory damages and attorneys’ fees (recent precedent notwithstanding) they are now taking away from songwriters in the Music Modernization Act.

But never fear–songwriters who are also Spotify stockholders will still have the stick of shareholder derivative suits to go after malfeasance in the boardroom. Shareholder derivative suits are in a very broad sense kind of like class actions, something Spotify is very familiar with. The class is stockholders and the defendants are often limited to the officers and directors of the company for doing things like, oh, say, committing massive acts of willful copyright infringement that probably could be criminally prosecuted if there were any prosecutors with the chutzpah to actually enforce the copyright law.

And once Spotify sells shares to the public, the insiders may control the infringement but they can’t control who buys their stock.

Since Mr. Ek seems to want to be just like Google, maybe he’ll be just like Google in another way, too. And remember–this is just the beginning of the disclosure of the inner workings of Spotify that will start to dribble out as its SEC disclosures become due and payable. And these supervoting stock classes are a very good way to demonstrate that you broke it, you bought it.

You want all the control? Well, you got it. And having all the control means having all the responsibility, too. Just ask Uncle Sugar.