As profitability returns to the recorded music industry, Glenn Peoples found some unexpected wisdom from one of the world’s greatest punk outfits, The Ramones. He draws lessons from the punk pioneers on how to navigate and understand music’s new and complex landscape

____________________________

Guest post by Glenn Peoples from Medium

I thought of the legendary punk band the Ramones a month or two ago when browsing through the latest IFPI (International Federation of Phonograph Industry) report on global recorded music sales in 2018. The band typically doesn’t come to mind when pouring over data like countries’ annual ad-supported audio streaming revenue (United States is #1) or a list of countries ranked by physical product revenue (Japan is #1).

The collective record business, comprised of labels in diverse markets around the globe, is continuing its four-year, upward path from a revenue abyss. So the song “We’re a Happy Family” (Rocket To Russia, 1977) popped into my head. A decade ago the music industry was thick with trepidation and worry. The mood is different today. Today companies are growing and money is returning.

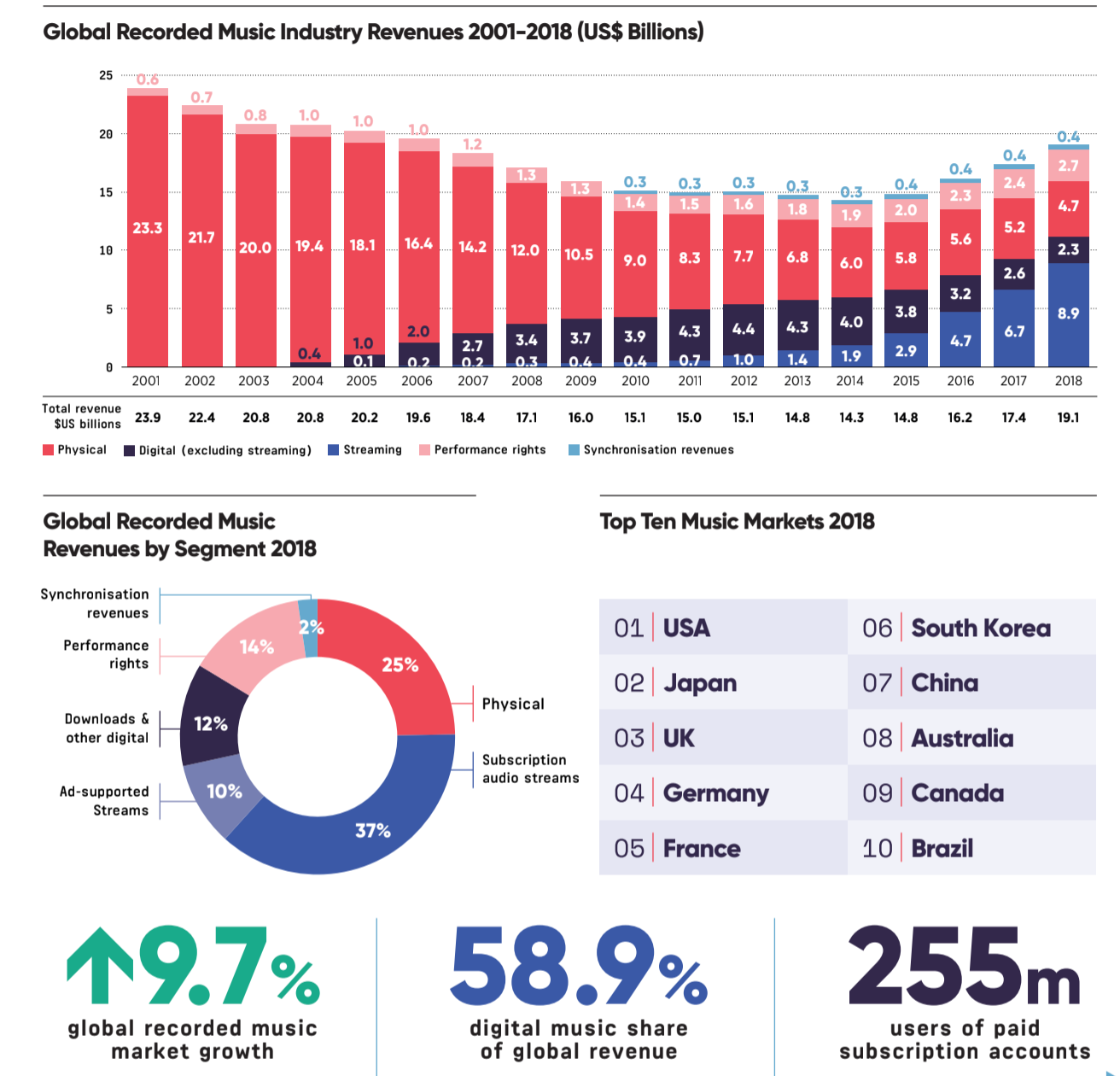

With revenues of $19.1 billion, 2018 was the fourth straight year of growth after a decade and a half of bleeding.

Around 2000, labels were complaining “Somebody Put Something In My Drink” (Animal Boy, 1986). Now they have “Something To Believe In (Animal Boy).

The intro in Primal Scream’s “Come Together,” with a snippet from the movie “The Wild Angels,” also came to mind:

“We wanna be free

We wanna be free to do what we wanna do

And we wanna get loaded

And we wanna have a good time

That’s what we’re gonna do”

Yes, people are having a good time (although amounts of elation vary).

Consumers are paying for music (although some—OK, many—people aren’t happy with streaming royalties).

Ad-supported streaming is growing (although too slowly, some might say).

In the United States, the Music Modernization Act, passed in December, will unclog some messes in licensing and will provide songwriters better royalties (although the “how” hasn’t been worked out).

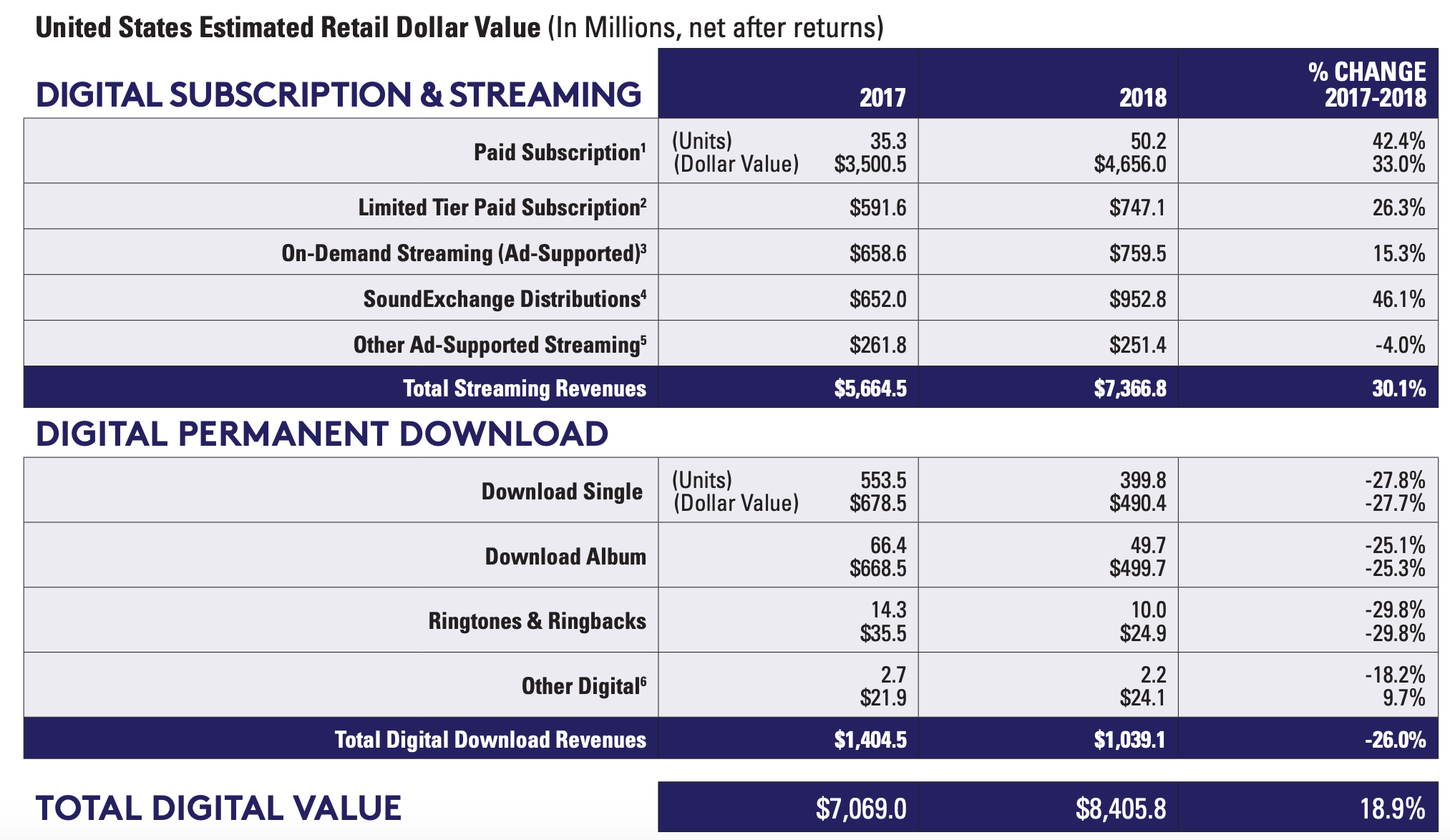

Streaming is the new cash cow and represents over half ($9.1 billion) of the record industry’s global trade revenue ($19.1 billion). Physical products amount to $4.7 billion—Japan alone had $2.05 billion.

Labels like streaming because it produces recurring, predictable revenue without the seasonal tides (neap in summer, spring during the holidays). Artists like streaming because….well, many artists appreciate the exposure streaming can provide, but they aren’t happy with the royalties.

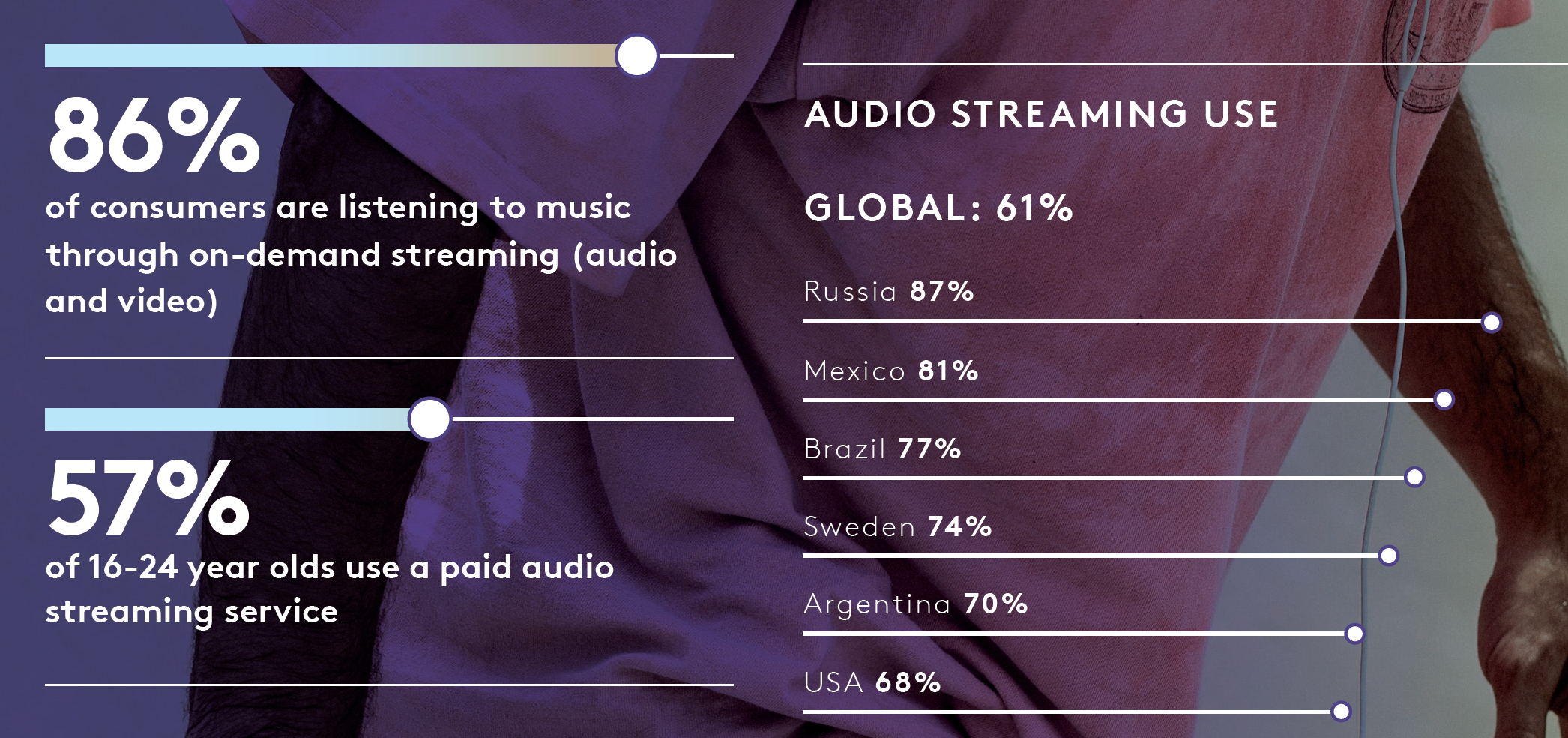

The lion’s share of streaming money, and thus the main driver of the global industry, comes from on-demand listening. Premium plans, both individual or family, represent the bulk of on-demand royalties. Advertising-supported services have grown, too, although they have a lower average revenue per user. The gap—called the “value gap”—between premium and ad-supported ARPU have drawn criticism from both rights owners and creators; YouTube, with high volume and low royalties, is the foremost target.

While streaming is headed up, CD and digital download sales are plummeting in the other direction. But this is nothing new. CDs never fell off the frequently-predicted cliff. (I recall a distribution executive saying ten years ago that Walmart would stop stocking CDs in the next year or two. Such a drastic phasing out of the CD never transpired.) Instead, CD sales have steadily declined each year for nearly two decades.

The market has adjusted accordingly. Brick-and-mortar retailers have continually dedicated less shelf space physical formats. Small record stores rely more on new and used vinyl than in previous years. (At the same time, mass merchants now sell a small number of titles on vinyl.) Labels have shifted resources away from brick-and-mortar retail in favor of digital products and online marketing.

The record business has reached an important point in its history. Now that streaming is the breadwinner, recorded music has turned a corner. Labels must build on that solid foundation by diversifying, taking risks, encouraging entrepreneurship, breaching into new markets, and keeping the business moving forward.

The Ramones, from Queens in New York City, produced 14 studio albums and four live albums in its 20-year recording career. Their first four albums in the ‘70s — the self-titled debut, Leave Home, Rocket to Russia, and Road to Ruin, all in just three years — are widely considered to be the band’s high mark, an influential body of work that created a template for punk bands to follow for decades. These cornerstone albums show a unique ability to carry a tune inside two-minute, furious bursts of buzzsaw guitar and a hard-driving rhythm section.

The most well-known song, “Blitzkrieg Bop,” is from the 1976 debut album. You might not know the song, but you’ve probably heard it: the song’s “Hey ho, let’s go!” chorus can be heard at sporting events!

And you’ve probably seen its unmistakable icon, the four members’ names circling an eagle, has been licensed to T-shirt makers that sell everywhere including mall chain stores — but the names are always (almost always?) the 1970s lineups: Joey, Johnny, Dee Dee, and one of the first two drummers, Tommy or Marky. I don’t recall seeing a T-shirt with Richie (the drummer between Marky’s first and second stints) or C.J. Ramone (the bassist who replaced Dee Dee from 1989 to 1995).

The band’s songs have a simplicity that led thousands of young musicians to say, “Hey, I can do that!” Over the years, though, the Ramones didn’t just figure out new ways to play the same three chords — although, let’s be honest, that describes a great deal of their catalog. Rather, they incorporated new sounds and themes. They brought in different producers who put their unique fingerprints on the band’s familiar songwriting. Although they are criminally overlooked, the Ramones’ ’80s and ’90s albums show the band never lost its genius. Much of their early ’80s output—End of the Century in 1980, Subterranean Jungle in 1981, and Pleasant Dreams in 1983—can stand against and sometimes exceed earlier material. From 1987 on the Ramones were like New Order: their albums were good but best for contributing a few songs to a “greatest hits” compilation.

“We’re a happy family

We’re a happy family

We’re a happy family

Me, mom and daddy”

“We’re a Happy Family” from Rocket to Russia, 1977

The lyrics to “We’re a Happy Family” can be misleading. The song is notabout a happy family unit. Rather, “We’re a Happy Family” humorously describes a dysfunctional family.

“Daddy’s telling lies / baby’s eating flies

mommy’s on pills

baby’s got the chills

I’m friends with the President

I’m friends with the Pope

we’re all making a fortune selling Daddy’s dope.”

Some people might argue record industry is a collection of dysfunctional relationships. Maybe so, but it’s easier to be happy when business is good.

The global family of record labels must feel like a happy family these days. Label revenues rose 9.7 percent to $19.1 billion in 2018 and marked their 4th straight year of improvement. Digital revenue grew 21.1 percent.

The extended family is happy, too. Adding music publishing and performance royalties, the global music business was worth about $28 billion in 2017, up from $26 billion in 2016, according to Spotify’s Chief Economist, Will Page. (I think it’s safe to say global revenues posted grew again in 2018.) Record labels, hurt more than publishers over the last couple decades of disruption, accounted for about three-quarters of the gain.

Sync revenue is up. Live music appears to be strong. The concert business is said to be recession-proof. Indeed, concerts suffered just one down year due to the AIG/Bear Sterns/Citi Group/Household Financial/Lehman Brothers/Moody’s/Standard and Poor’s/Fitch Group/Fannie Mae-and-Freddie Mac honorary Great Recession.

“Hang on a little bit longer

Hang on ’cause you’re a goner”

“Locket Love” from Rocket to Russia, 1977

“Locket Love” is about a poisoned relationship. It’s a fitting metaphor for consumers’ disaffection with the compact disc.

Compact disc, you’re a goner. Global physical revenue dropped 10.1 percent in 2018. (Vinyl sales, although a small part of the business, continue to rise.) And it will keep dropping.

But don’t except CD sales to go to zero; if the cassette can have a small comeback, the CD can keep a small corner of the music marketplace. There will be diehard enthusiasts. Cars have CD players. Home audio systems have CD players, the format will hang around. Record stores continue to carry good titles in $1 bins. A small brotherhood of CD buyers will keep the flame alive. As an example, see the recent comments by the New York Times’ Ben Sisario about his preference for CDs: “You push a button, the music plays, and then it’s over — no ads, no privacy terrors, no algorithms!”

Perhaps an underground community of ‘90s-era boombox aficionados will appear, just as demand for ’70s and ’80s pre-CD boomboxes has gone berserk (take a look at eBay). And let’s not forget that CD sales are still strong in Japan, the world’s second-largest music market behind the United States. But formats have a life cycle; CDs are in the late stages of the maturity phase. Both indie and major retailers carry few CDs these days.

“Glad to see you go, go, go, go, goodbye

Glad to see you go, go, go, go, goodbye

Glad to see you go, go, go, go, goodbye”

“Glad to See You Go” from Leave Home, 1977

“Glad to See You Go” lyrics read like a slasher horror film — typical for the band:

“Going to smile, I’m gonna laugh

you’re going to get a blood bath

and in a moment of passion

get the glory like Charles Manson.”

Indeed, the digital download is in a bloodbath right now.

Global digital download sales plummeted 21.2 percent and accounted for just 12 percent of total revenues in 2018, according to the IFPI.

Sales are falling faster in the United States: in terms of both units and revenue, downloads fell between 25 and 28 percent last year.

The download had a good run. If you start with Napster and continue through iTunes, the download has had a solid 20-year run. Downloads were a necessary stepping stone between physical items and cloud computing.

But I can barely be bothered to download a track these days. I don’t even download the digital tracks that come with my purchases on Bandcamp. Instead, I stream the songs within the Bandcamp app knowing I can download the tracks if/when I choose. But I can’t be bothered.

Oh, how we were wrong about digital downloads. A decade or more ago, many learned people in the music business pondered a future where a small, portable device had enough memory to hold thousands of albums and hundreds of millions of tracks. (Call it Jobs’ Law.) Streaming services existed but mass adoption was an abstract event too far in the future.

A combination of (then rampant) peer-to-peer distribution and large-capacity storage devices was frightening. “Who would bother to buy music?” they thought. You couldn’t swing a dead cat at a music business conference and not run into a panel on how teens of the ’00s were a generation lost to piracy. Occasionally a panel would have actual teens talking about how they listen to music. The middle-aged audience listened with both awe and fear. It was a fair question, though, and it presaged today’s unlimited access to music.

Fast forward a decade. Streaming services create far more value than piracy can offer. A few hundred million people pay some amount of money ($10/month here, more in some places, less in some places) to rent rather than own. Many people have moved beyond the download and prefer the access model over ownership model. (Video streaming services such as iTunes and Amazon make renting superior to owning.) The resurgence of vinyl LPs is not incongruous to consumers’ shift to streaming; people occasionally buy, but, by and large, they’d rather not buy.

Downloads have value in a few scenarios. If you lose a cell signal and haven’t downloaded songs from your streaming service, you’re out of luck. (Premium streaming services offer downloads to mobile.) A download works as long as your device has power. And if you’re still into downloads, you can fit a LOT onto today’s thumb drives. If your car stereo has a USB input, for example, you can take your music collection—it may include concert bootlegs, unlicensed recordings, and DIY remixes not found on streaming services—on the road.

And that lost generation? They’re now the 25–34 demo—the age group with the highest adoption rates of paid streaming. Not so lost after all.

“You’ve gotta fight to stay independent

I’ve got my pride and I’m going to defend it”

“High Risk Insurance” from End of the Century, 1980

How does a band follow its prototypical albums without copying itself? Famed producer Phil Spector, a progenitor of the “wall of sound” style, worked with the Ramones for the 1980 album End of the Century. The album may not have reached Sire’s commercial goals, but Spector left a damn good album for posterity. I forget where I read it, but I recall somebody saying Spector had them play songs endlessly to tire them out and play the songs at the speed he wanted.

“High Risk Insurance” is a peppy song with the sort of military themes Dee Dee wrote into many of his songs (he was raised in Germany). “Got endurance, I was trained / I got my sights adjusted and my telescope aimed / everybody wants an explanation / got no love for the enemy nation.”

Independence in digital music isn’t easy. When SiriusXM’s acquisition of Pandora was consummated in February, the number of standalone music streaming services dropped by one. (Two months earlier, Chinese tech giant Tencent had spun off Tencent Music Entertainment with an IPO.) From a financially a percent of revenues, are high enough to make music a loss leader for books, consumer electronics, etc. (Labels are hesitant to give margin relief without getting value elsewhere, such as free advertising if available.) At some unknown point, a streaming service will scale to a tipping point and make a profit on each incremental subscriber.

But having some 75–80 million monthly listeners won’t necessarily result in healthy financials. Launched in 2005, Pandora was an innovator that brought personalized Internet radio to the masses. The company went public in 2011. In spite of margins smaller than tech companies with similar market shares, investors gave Pandora a pass—typical with growing tech companies—as the losses mounted. But seven years after its IPO, Pandora was acquired by SiriusXM, a once-struggling company that turned the corner and became profitable.

Financial and philosophical questions abound regarding corporate consolidation. Do people want a diverse, competitive streaming market or an oligopoly that characterized the download market? This is an important question to ask. A philosophical question, yes, but also a vital question.

Do people want music-first, standalone streaming companies or the streaming services of some of the largest, most-valuable technology companies in the world? Do music consumers benefit from a standalone service that lives or dies on the strength only of its music/audio platform?

Consumers don’t have much of a say in the matter; they have little control over the bankruptcies and acquisitions that will shape the market. People will not subscribe to a streaming service for idealogical reasons. Consumers tend to use a product without getting political—one notable exception was Pandora listeners’ lobbying when the company faced a life-threatening royalty rate increase in 2008. Nobody in a bank’s M&A department are asking for listeners’ opinions on future dealmaking.

But record labels and music publishers, due — by statute — certain amounts of royalties, do have a strong ability to shape the streaming market. Content costs and, thus, gross margin will affect services’ financial health and influence market diversity. This holds across the marketplace. Rights holders might not want to play favorites. They might prefer to remain platform agnostic. Even so, labels still have the power to shape the marketplace. It’s not like Adam Smith’s invisible hand will let events play out. Digital media doesn’t act like a purely competitive market. Government protections exist and skew outcomes.

“Mr. Programmer

I got my hammer

I’m going to smash my, smash my radio”

“We Want the Airwaves” from Pleasant Dreams, 1981

Ayear after the Phil Spector-produced End of the Century, the Ramones following with the sneakily pleasing Pleasant Dreams. Produced by Graham Gouldman of 10cc, the British band best known for its 1975 soft rock hit “I’m Not In Love.”

The Ramones’ warned of rock music’s decline on their under-appreciated 1983 album, Pleasant Dreams. They were a few decades too early, however; rock radio would eventually suffer at the hands of the Internet. Rock would nearly disappear from the charts, too, spurring one “Is rock dead?” headline after another. But rock music, in its many forms, can be found everywhere from festivals to television commercials.

In any case, “We Want the Airwaves” can be written for the playlist generation as “We Don’t Want the Airwaves (We Want Onto Your Playlists and Internet Radio Stations).” Playlists are the streaming equivalent to broadcast radio (as are the radio stations available on streaming services). The radio industry constantly touts listener metrics that reveal high penetration rates—always around 92 or 93 percent per week. But people are (figuratively) smashing their radios.

Too Tough To Die, released 1984, and Animal Boy, out in 1986, followed Pleasant Dreams. The band had become more defiant (“Too Tough to Die”), angry (“Somebody Put Something In My Drink,” the lead-off track on Animal Boy, and one of a few written by short-tenured drummer Richie Ramone), and political (“My Brain is Hanging Upside Down”). Joey’s voice had become rougher with age. Dee Dee’s singing became unintelligible (without peeking, try to figure out the lyrics to “Warthog”). You won’t get many positives comments for Halfway to Sanity (1987), my least favorite of the band’s studio albums. But 1989’s Brain Drain was an improvement and received some commercial success for “Pet Cemetery” written (by Dee Dee Ramone and frequent collaborator Daniel Ray) and recorded for the Stephen King movie of the same name. In all, the Ramones had a sneaky great music in the ’80s.

“Only thing that you regret

You need more time to forget

And you don’t come close

You don’t come close

You don’t come close”

“Don’t Come Close” from Road to Ruin, 1978

Rare is the Ramones song simpler than “Don’t Come Close.” It’s one of many peppy songs on Road to Ruin, the third of the band’s celebrated first four albums.

Startups at the intersection of music an blockchain don’t come close—to be successful businesses, to providing value for their token holders, to changing the music business. Not just yet, and for some of them, not ever.

After spending a few months looking at startups in music/blockchain, the song “Time Bomb” (Subterranean Jungle, 1983) comes to mind, (not “Time Bomb” by Rancid), as does “Every Time I Eat Vegetables I Think of You” (Subterranean Jungle). Many of these companies lack the preparation and focus of the average music startup. It’s as if writing a white paper—the crypto world’s hybrid business plan-prospectus—automatically adds legitimacy to an endeavor. It doesn’t.

The tokens of the 13 music-blockchain startups listed at MyMusicToken have a combined value of $27.3 million at the current, depressed Ethereum price. One of these startups was ridiculously valued at over $115 million when Ethereum prices peaked in January 2018. I wouldn’t buy a token from any company in the group until it shows discernible progress.

But I’ll add some positive, generous caveats:

- To be fair, music blockchain companies are operating well ahead of the curve—an inverted curve?—and a low survival rate is to be expected.

- Blockchain technology has value from the artist point of view: transparency of the sale/stream and payment; immediate payment; minute transaction costs.

- Prominent companies are using or considering the use of blockchain technology, such as JP Morgan, Amazon, Microsoft, Comcast, Walmart, Seagate, HTC, MetLife, State Farm, Bumble Bee Foods, …the list goes on.

- Forrester sees much progress in blockchain technology. The analysts notes an “abundance of platforms, with improved tooling and services” and an expects to soon see a “steady stream of enterprise-relevant launches.”

But blockchain has a long way to go for widespread adoption in music. One of the most glaring problems is the token, a platform’s unit of value. An artist paid in tokens needs a functioning exchange to cash out in fiat currency such as the U.S. dollar. Some startups want to create a marketplace in which tokens can be exchanged for goods such as stems and loops. It’s a good idea in theory: a new currency accepted throughout a marketplace, somewhat like the BerkShare in the Berkshire Mountains of Massachusetts.

One big blockchain problem is how companies lure token — sometimes implicitly, too often explicitly — with the chance a token will appreciate in value. In other words, token buyers are often speculators, not people who actually want to use the tokens for their intended purposes, not people who want to participate in the business.

But setting aside the profit motive, tokens that cannot travel off platform could become worthless. When you obtain a token, you hope somebody is making a market. In other words, somebody needs to buy your token for you to obtain the fiat money (dollars, euros, etc.) that pays your utility bills, puts gas in your tank, and allows you to eat. Maybe someday all grocery stores will accept Ethereum. Until that happens, you want fiat.

Imagine being a Wall Street bank caught with “toxic assets,” the name given to subprime mortgages stuck on a bank’s balance sheet. Just as you don’t wouldn’t want to be left holding a mortgage when an owner defaults, an artist wouldn’t want to hold tokens that could plummet in value before being cashed out for fiat currency (unless landlords start accepting crypto). In effect, being paid royalties on a blockchain platform turns every artist into a cryptocurrency speculator, if only for a moment.

“You got to learn to listen

Listen to learn

You got to learn to listen

Before you get burned”

“Learn to Listen” from Brain Drain, 1989

“Learn to Listen” is a warning about drug use, not the challenges podcasts must overcome. It appeared on Brain Drain, Dee Dee Ramone’s last with the band. Although Dee Dee contributed usually most of an album’s songwriting, “Listen to Learn” was written by the other three band members (with frequent collaborator Daniel Rey) without Dee Dee. The bass player turned solo artist struggled with drug use and died from a heroin overdose in 2002.

People who don’t listen to podcasts need to learn about them. Understanding and education are clearly big problems. People can simply listen to podcasts to learn about them. Just listen to a few.

Companies jumping into podcasts must listen to consumers. Invest in programming people want. Anticipate demand for a type of podcast that doesn’t yet exist. If you want to create the 90 millionth true crime podcast, go right ahead. But you might want to follow the old baseball adage “hit it where they ain’t.”

Podcasts are widely popular, and the number of podcasts is exploding. In the music world, Sony Music just signed up Adam Davison (of “Planet Money” fame) and producer Laura Mayer to “find and develop original podcast talent and programming.” So, a bunch of podcasts about Sony artists and music? This is a good move by Sony. Davidson does fantastic work. Atlantic Records is doing podcasts. Rhino Records has a long-running podcast. Portia Sabin from Kill Rock Stars has being the podcast The Future of What for years. Musicians Aimee Mann and Ted Leo have a cool podcast, The Art of Process that covers the creative endeavor.

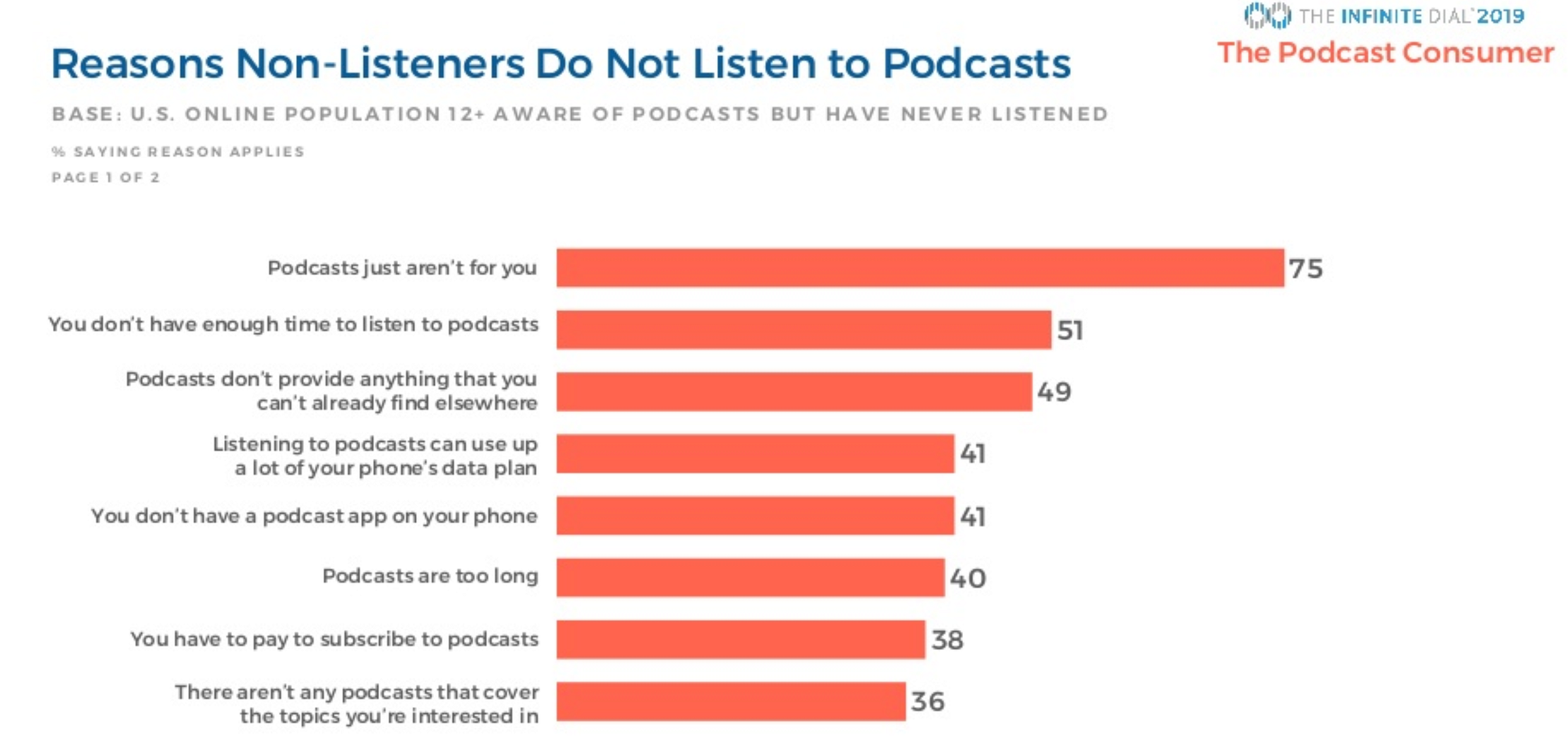

Edison Research found the second-leading reason non-listeners do not listen is they “don’t have enough time to listen to podcasts.” Everybody has free time, whether in the car or doing dishes. Perhaps people don’t think of podcasts as a substitute for talk radio—even though they’re an obvious substitute and often the same thing (many popular podcasts are broadcast on NPR).

38 percent of people surveyed believe they have to pay to listen to podcasts. Mostly not true. Podcasters run adds and take donations. Many of them don’t like paywalls (in part because they have sponsors who want the widest distribution possible). Just last month, many top podcasters pulled out of Luminary — billed as the Spotify of podcasts — when they found out their shows were being offered behind a paywall.

People also believe podcasts don’t provide anything they can’t get elsewhere. That’s true in a sense. Many popular podcasts are merely downloads of programs originally made for broadcast radio. Programs heard on NPR are among the most popular podcasts. TED Radio Hour, heard on NPR stations, is a scripted show built around “TED talks” of similar subjects. But an incredible amount of quality podcasts are not available elsewhere: true crime stories, history, politics, et al. Joe Rogan Experience, The New York Times’ “The Daily,” “Pod Save America,” and “Making Sense with Sam Harris” are among some of the most popular podcasts not connected to broadcast radio or television.

Education will be important. Podcasts hold opportunity for artists and labels to promote themselves, their music, their tours, etc. But more people need to start listening for music podcasts to have the greatest impact.

“Not a millionaire

Not doing too bad

When we sell the Camaro

I will be glad”

“Funky Man” from Dee Dee King’s Standing in the Spotlight, 1989

Dee Dee Ramone, bass player and (I would argue) the group’s principal songwriter, left the Ramones in 1989. He would soon release a collection of rap under the name Dee Dee King. A fictional character? Another identity?

Standing in the Spotlight is a divisive album. One one hand, Dee Dee King’s songs are terrible and some people can hardly stomach them. On the other hand, the songs are terrible but some Ramones fans purchased the album anyway. (I admit to owning the album as well as the “Funky Man” 12″ single.) AllMusic predicted the album “will go down in the annals of pop culture as one of the worst recordings of all time,” although to be fair Standing in the Spotlight was released well before Pro Tools and digital distribution became widely available.

“Funky Man,” released as a 12″ single, is a clumsy attempt at New York hip hop. A few lines merit attention, however. “Not a millionaire, not doing too bad,” he says. Indeed, Dee Dee was the epitome of a working music. After his short-lived rap career, he launched Dee Dee Ramone and the Chinese Dragons, and The Remainz, and released solo albums under his name (Zonked! is a good one).

Thirty years later, Standing in the Spotlight is merely an aberration — albeit of fun aberration — in an otherwise stellar career. Dee Dee continued writing songs for the band after he was replaced by Christopher Joseph Ward, we assumed the name C.J. Ramone— he took on the Ramones surname and trademark black-leather-and-ripper-jeans uniform. He continued to record music under his original stage name, but Dee Dee King was never seen again.

“Oh, Tipper, c’mon

Ain’t you been getting it on?

Ask Ozzy, Zappa or me

We’ll tell you what it’s like to be free”

“Censorshit” from Mondo Bizarro, 1992

The Ramones’ final two albums have great moments, too. I don’t have a music metric to go along with these lyrics. Since the band’s ’90s output lands somewhere between ignored and forgotten, I wanted to include “Censorshit” from Mondo Bizarro. The song beautifully tears down the Parent Music Resource Center’s ginned-up controversy over explicit content warnings on albums (those black stickers seen on CDs….which some artists said actually helped their sales). The lyrics are directed Tipper Gore, a co-founder of the P.M.R.C. and wife of then-Senator from Tennessee, and future vice president, Al Gore. The congressional hearing is the stuff of legend. Watch the 30-minute testimony of Twisted Sister’s Dee Snider with his long, curly blond hair flowing over his cutoff T-shirt.

The band didn’t slow down. Near the end of their career, the Ramones recorded a covers album, Acid Eaters, that show influences ranging from psychedelic rock (Love’s “7 and 7 is,” Amboy Dukes’ “Journey to the Center of the Mind”) to classic artists (The Who’s “Substitute,” The Rolling Stones’ “Out of Time,” Bob Dylan’s “Out of Time”). Years before Acid Eaters, they released a cover of the 1910 Fruitgum Company’s bubble-gum pop tune “Indian Giver” (it was a B-side to “A Real Cool Time” and appeared on the Ramones Maniacompilation released in 1988).

Subterranean Jungle has three excellent covers: “Little Bit O’ Soul” by The Music Explosion, which reached #2 in 1967; “I Need Your Love” by Bobby Dee Waxman; and “Time Has Come Today” by The Chamber Brothers. Other albums featured “Do You Wanna Dance?” (written and recorded by Bobby Freeman), “Surfin’ Bird” (The Trashmen’s 1963 hit), “Chinese Rock” (by punk legend Johnny Thunders), “Palisades Park” (written by Chuck Barris and recorded by Freddy Cannon), and “Baby I Love You” (the Ronette’s 1964 hit),

“I used to be on an endless run

Believe in miracles ’cause I’m one

I have been blessed with the power to survive

After all these years I’m still alive”

“I Believe in Miracles” from Brain Drain, 1989

What better words could apply to today’s music business? Bruised and beaten by peer-to-peer piracy and the unbundling of the album—single tracks for sale—labels are currently in their fifth-straight year of growth. Global revenues in 2018 were the highest since 2007—without adjusting for inflation—and, I think it’s safe to say, will grow to over $20 billion this year.

Maybe “miracle” is too strong a word to describe the canary’s escape from the coal mine, so to speak. People throughout the industry understand a four-year upswing doesn’t make a recovery. Hurdles still exist: licensing new business models; implementing aspects of the Music Modernization Act; figuring out what to do with smart speakers; etc. etc. etc.

But a turnaround is in progress. Since Napster launched in 1999, the music industry was “All Screwed Up” (Brain Drain, 1989) and probably felt like a “Teenage Lobotomy” (Rocket to Russia, 1977). But everyone—labels, publishers, managers, artists, digital service providers—figured out how to run a digital business, rejected any urge to say the Internet will be the “ Death of Me” (Halfway to Sanity), all the while telling itself “It’s Gonna Be Alright” (Mondo Bizarro, 1991).

Glenn Campbell: I write. I do numbers. I write about numbers. Working in and around the music business for a few decades.