An emerging market which is taking its sweet time to emerge, Ed Peto here offers us a view of the India’s digital music industry, taking into account both its enormous market potential, and the many barriers which stand its way.

_______________________________

Guest post by Ed Peto of Outdustry

This article, authored by Outdustry’s Ed Peto, originally appeared as a feature in the Music Ally Report on June 28th 2017. It represents the start of Ed’s Masters thesis research into the Indian music market for the Berlin School of Creative Leadership MBA. You can also see Ed curating/moderating the MIDEM 2017 India panel here (Music Ally write up here).

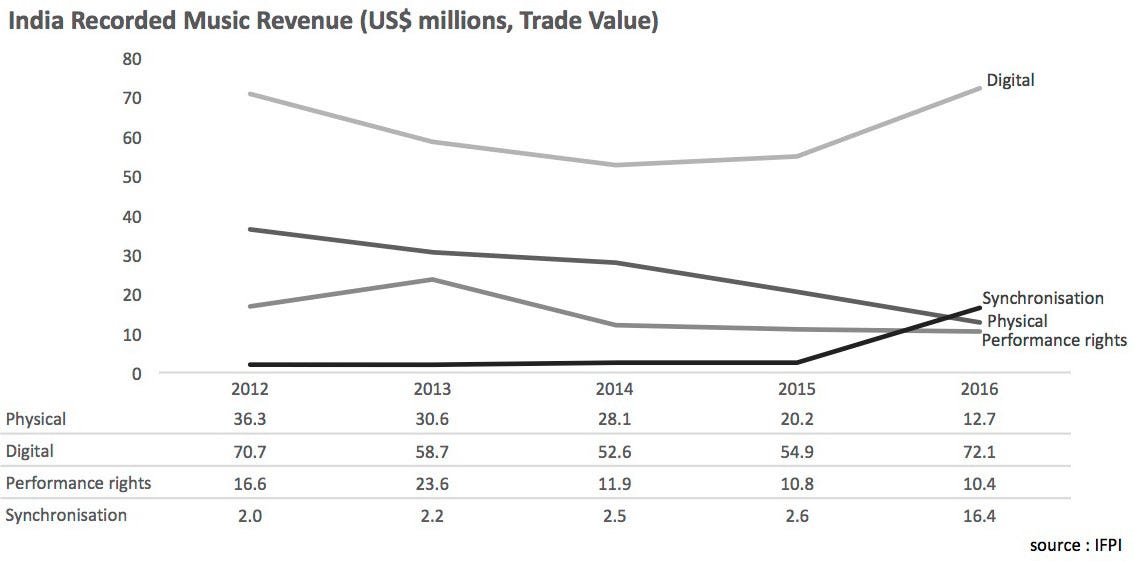

India’s recorded music industry generated just US$0.09 per capita in trade revenues in 2016, making it the most poorly monetised music market currently being tracked (IFPI), tied in last place with the failing state of Venezuela (US$0.09), behind Indonesia (US$0.14), China (US$0.15) and the Philippines (US$0.18) (For reference, US is US$16.41, UK is US$19.42, Japan is US$21.67).

An optimist would rightly point out that with a population of 1.27bn India has had more heavy lifting to do than most, and that obviously there is enormous room for growth, but even amongst the giant emerging music markets India is taking its time to emerge. This same optimist could go on to point out that it is because of this slow emergence that India is actually poised to leapfrog both desktop computers and fixed line broadband — having only ever reached 34.8% fixed line internet penetration — and move straight into the age of unlimited 4G mobile data consumed on cheap Chinese Android smartphones (currently with 40% of the market) — A high capacity, low barrier-to-entry, mobile-only ecosystem of potentially unparalleled long term value. This digital utopia exists only with a very long view in mind, however, with enormous obstacles to overcome in the meantime.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Digital India initiative, launched in 2015, may have “universal access to mobile connectivity” as a central pillar but India’s mobile infrastructure — microwave spectrum, cellular towers, fibre optic network — is still not fit for purpose, with dropped calls, poor coverage and, until recently, expensive data costs being the norm. The September 2016 launch of mobile provider Reliance Jio, however, lit a fire under the telco market, with the self-described “world’s biggest startup” throwing a mind-boggling US$23bn (1.5 lakh crore INR) into its own 4G fibre optic and tower infrastructure, using the spare change to spark a race-to-the-bottom pricing war in which data has plummeted to as little as US$0.10 (6 INR) per gigabyte (averaged across the major provider offerings). Beyond netting Reliance Jio more than 100m subscribers within 6 months of launch, this pricing war has smashed through the demographic glass floor, making data affordable beyond the middle classes and tier 1 cities for the first time.

India is now set to have 420m mobile internet users by June of this year, and while infrastructure and other demographic issues (e.g. myriad regional languages) will continue to dog this growth, this already seems like the kind of scale that should be able to support a nascent digital content eco-system. Unfortunately, as betrayed by the per capita statistic at the top of this article, so far this burgeoning mobile audience is incredibly low value. India attracted just US$1.19bn (76.9bn INR) in total digital advertising spend in 2016 and the concept of premium content subscriptions has yet to arrive in any meaningful way. If even the all-conquering Bollywood film industry has failed to establish a digital business model to this point, then the over-crowded market place of freemium digital music service providers (DSP) — Saavn, Gaana, Wynk, Jio, Hungama, Apple Music, Google Play Music, Amazon Prime etc — really have their work cut out.

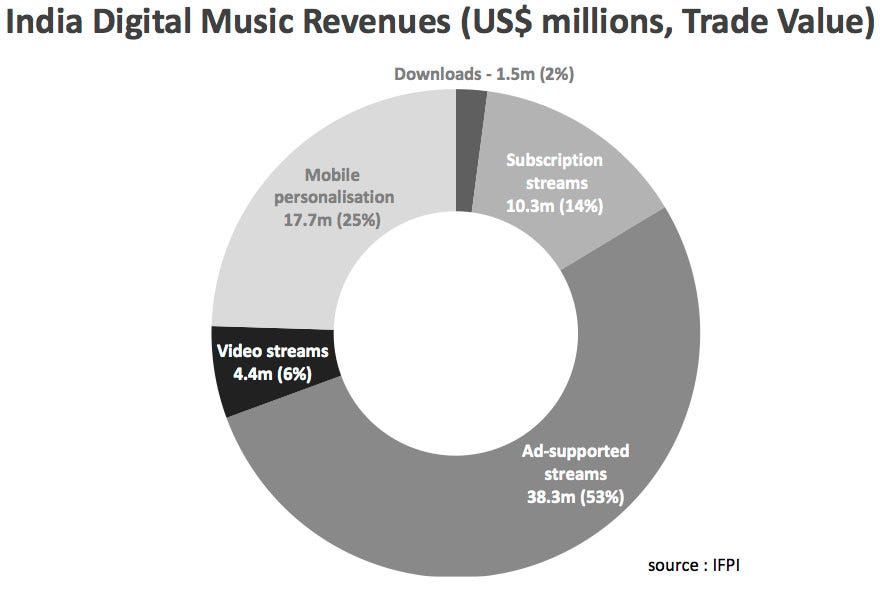

With a reputed 60m MAU across all DSP, the economics of digital music do not yet meet the comfort levels of wary major rights owners on a purely ‘transactional’ basis — i.e. a rev share of scarce advertising dollars, or a low per stream minimum in the region of US$0.0011 (0.07INR) — meaning the vast majority of India’s US$72m (IFPI) in digital revenues comes in the form of lump sum minimum guarantees (MG), negotiated based on perceived catalogue market share, primarily of Bollywood music, with legacy revenue expectations from the physical and ringback tone era. While India has a huge diversity in music — Indipop, regional folk, devotional etc — Film music still has around 70% market share concentrated across a handful of major Bollywood rights owners, with any non-film music finding it hard to participate in this MG driven market place, consigned instead to the world of negligibly small transactional per stream returns. The recorded music industry proper is yet to emerge from under the shadows of the film industry.

In short, it is an interim digital musical economy, a transitional phase in which an over-proliferation of DSP are stuck between large label MG on the one side and a painfully-slow-to-emerge digital music economy on the other. Streaming revenues grew by 52.9% to US$53m in 2016 (IFPI), however, helping India’s music industry to an overall 26.2% growth after 3 years of contraction, so things now finally seem to be on an upward curve. For DSP, though, deep pockets are required, be it from giant telco parent companies or long sighted VC backers.

The crucial figure is the US$10.3m (IFPI) in subscription revenues. At a typical subscription price point of US$1.5 (99INR)/month, this figure suggests significantly under 1 million subscribers in total across all DSP. In the coming years, as with everywhere else in the world, subscriptions are where the focus will be, although in the short term it is an incredibly tough sell. Since its 2008 launch in India, YouTube has become a catch-all platform for free content consumption — TV, film, music, UGC — earning it an audience of 180m MAU, meaning more than a third of the entire Indian internet user base of 460m visit the platform each month. Of late, however, major broadcasters and film studios have been removing their content and building standalone OTT offerings with the ultimate aim of monetising via subscriptions. As a music platform, though, YouTube is still where the vast majority of digital music consumption takes place as free video streams. Along side this, an estimated 78% of internet users have used stream-ripping software within the previous six months. In short, free access and free ownership are both assumed, with understandably slow progress being made in convincing users that more value lies behind a subscription paywall.

Looking forward 5 years to 2022, India will likely have overtaken China to become the most populous nation on Earth, with some 1.4bn people; It will also likely have over 1bn mobile internet users, 80% of which will be on 3G/4G at rock bottom data prices, with 5G in the early stages of rollout; The economy will be largely cashless (despite the recent demonetisation fumble), with frictionless digital payments being the norm; India’s economy is also expected to be consistently posting over 7% annual GDP growthduring this period, maintaining its top spot as the fastest growing major economy in the world.

The list of impressive numbers goes on indefinitely, making it an undeniably exciting market. The real deal-breaker, however — and the one that almost all major rights owners and (the overwhelming majority of) platforms are betting on — is that premium content subscriptions need to take off. While digital advertising spend will surpass US$5bn (322bn INR) by 2022, this is not enough to support the huge range of content and services required to satisfy a billion person internet. Heavy bets are being made as we speak, but the crowded landscape of telcos, music services and video platforms will be seeing a brutal period of consolidation over the next five years. 2022 India may potentially be a digital utopia, but it will only be a handful of deep-pocketed, all-conquering giants able to survive long enough to enjoy it.

Subscribe to the Outdustry newsletter for sporadic updates and analysis on the Chinese, Indian and other emerging markets, as well as Outdustry’s work as a market-leading China music industry services company. Alternatively you can contact us here, or follow us on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.