Chris Castle breaks down in detail just how harmful the regulations imposed by the government surrounding mechanical license royalty rates are, and the value of advocacy in righting the ship to create a more balanced industry.

_____________________________

Guest post by Chris Castle of Music Technology Policy

There is a certain Truman Show aspect to songwriter royalties–the government sets the royalty rates, not arms length negotiation. But it doesn’t have to be that way, we just accept the government’s role in songwriting because it is the way it has always been for living songwriters and many generations before. The entire statutory rate system is like if Rube Goldberg and Franz Kafka met in a nightmare and disrupted the banking system.

If you’re a songwriter born after 1975 and are not a student of history, you may not fully realize the long-term harm of statutory mechanical rates. If the statutory rate seems improbably low to you, you’re right. It is.

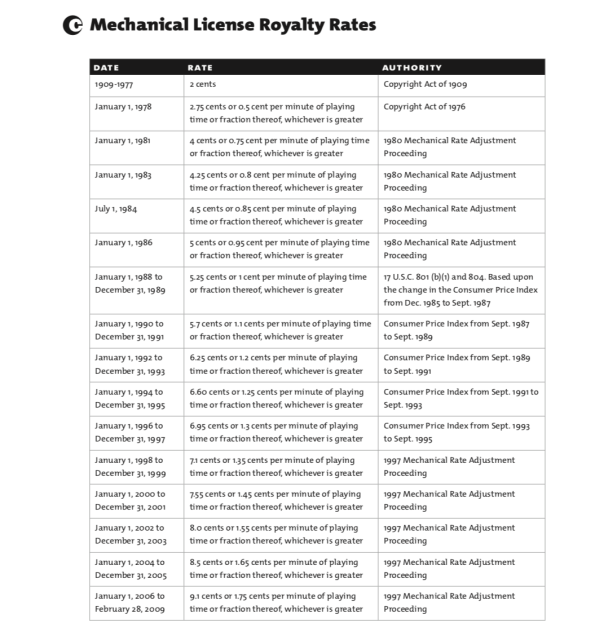

You also may not realize that one good reason that the compulsory license rate for physical and downloads is so low at 9.1¢–and the streaming mechanical is so absurdly low–is because of the extraordinarily low government rates that came before. And this is where a page of history is worth a volume of logic: From 1909 to 1977 the government set the “free market” compulsory mechanical royalty at 2¢.

That’s right–the government froze the compulsory mechanical rate at 2¢ for 68 years. Songwriters are still struggling to recover from this intervention.

After tremendous effort and years of fighting, the statutory mechanical rate increased in pennies but arguably not in buying power. In 1976, the government’s 2¢ rate was increased to 2.75¢, and then gradually rose to 5¢ every two years for the next ten years (largely due to relentless lobbying efforts of songwriter Hoyt Axton). That new royalty rate was the only actual increase that songwriters got. In 1988 the then 5¢ rate was prospectively indexed to inflation (the Consumer Price Index). The rate began to gradually increase due to the indexing. But indexing really just preserves buying power. While it is better than a cut, indexing is a sop for the government wanting you to think they are actually giving you something that improves your life.

There should have been an increase in 1978 retroactively to 1909 which would have been the fair thing to do.

If the rate had been indexed to 1909, the current rate for physical and downloads would be something like 52¢–and again that 52¢ is no actual increase in the songwriter’s buying power. Inflation adjustment is just increasing 2¢ in 1909 dollars for inflationary increases in the CPI to the same value in 2019 in current dollars according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But–that indexing stopped in 2006 for reasons that are unclear. That’s why the mechanical rate has been frozen at 9.1¢ for 13 years. According to Billboard, the freeze was agreed by a private negotiation between the National Music Publishers Association and two major labels and then ratified by the Copyright Royalty Board (which is how these private deals become law). Based on “Phonorecords III” or the Determination of Rates and Terms for Making and Distributing Phonorecords. Docket No. 16-CRB-0003-PR (2018-2022) the 9.1¢ rate will be in effect until 2022. Even if the 9.1¢ rate were itself indexed to inflation starting in 2006, the 9.1¢ rate would be worth 11¢ today.

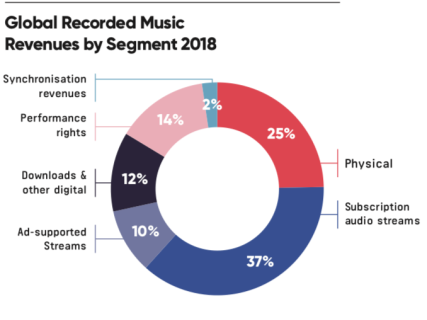

While not as widely reported in the press as streaming (which depends on the presence of an Internet architecture that is simply not present in many parts of rural America or large swaths of the rest of the world), physical comprises 25% and digital downloads comprise 12% of global music revenues in 2018 according to the IFPI. That’s not nothing and is still a solid chunk of mechanical royalty revenue for songwriters and publishers.

These frozen rates likely have an indirect relative impact on all other statutory rates for songs or near-statutory rates in the ASCAP and BMI consent decrees. (That’s what economic experts are for.) When the government freezes wages but imposes a compulsory license, they also identify songwriters as a class of people who the government has decided are not entitled to negotiate for any value-based increase in their compensation.

On streaming, the headline numbers brag of a 44% increase (currently being appealed by some of the streaming services)–but this is still a rate that starts two to three to four decimal places to the right. Frozen rates create a distortion even in the government’s fake market for songwriters just like piracy benefits Spotify’s growth strategy by creating the illusion that the licensed service’s real competition is with “free”. Songwriters suffer all of these low rates (including the currently frozen physical rates) in the shadow of the 68 year winter from 1909-1978.

But are you ready? When you compare the historical rate of 2¢ to increases in the CPI from 1909 to 1978 when the statutory indexing of the government’s royalty rate started, something strange comes out.

The actual 1978 mechanical would have been a negative 11¢.

So at the current 9.1¢ rate, songwriters haven’t broken even yet compared to 1909. And remember–that’s just to get the same buying power as the rate had in 1909. It’s not an increase.

Remember–the current mechanical rate for physical and downloads has already been frozen for 13 years. In Phonorecords III, that rate will be frozen until 2022 for a total of 16 years. It also must be said that despite the full throated protests over Spotify, Amazon and Google appealing the Phonorecord III streaming rates, the 9.1¢ rate does not seem to be part of that appeal. The issue was, however, raised by George Johnson, a songwriter and one of the appellants (at p. 13 of his brief):

Adjust the 9.1 cent mechanical rate, for 69 years of unrecognized inflation6 from 1909 to 1978 which is self-evident7 and easily calculated by any government economist. The CRB erred by not adjusting the rate to 2019 standards. Additionally, the 9.1 cent rate set in 2006 has not been raised for inflation, or any other reason, in Phonorecords I, II, or III. Since this is an administrative appeal and the courts consider copyright a public right, we pray the Court can immediately factor in lost inflation by using government inflation numbers at the Bureau of Labor Statistics or St. Louis Federal Reserve and make a final determination.

Even if these services sold physical goods or downloads they…ahem…don’t pay a separate mechanical as that mechanical is included in the wholesale price. And you wonder how the rates stayed at 2¢ from 1909 to 1976? Because someone let them stay frozen.

There’s an easy answer to why the government set songwriter price controls with no increase for 68 years. The feds didn’t do that to anyone else whose wages and prices they froze.

The government got away with it because nobody fought back.