In this recent article, Marc Ribot explores how the tragedy at Oakland’s GhostShip lofts is indicative of a broader issue concerning the marginalization of working artists.

____________________________

Guest post by Marc Ribot on The Trichordist

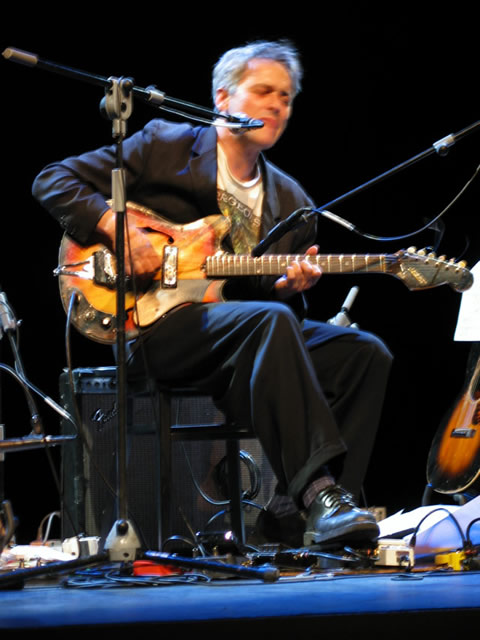

Marc Ribot is an American Musician a member of NYC artists rights group MusiciansACTION http://musiciansaction.org/. Photo by Webb Traverse at English Wikipedia (Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The initial horror evoked by Oakland’s GhostShip fire is now turning into self questioning and anger at those who placed the victims in harms way.

Yes, there will be individuals —landlords, inspectors, event organizers —held to account.

But the political context of this tragedy is that artists — not only musicians, but graphic artists, photographers and other content creators–have been placed in a condition of risk and precarity by Silicon Valley’s trashing of the copyright laws— a mass expropriation of value which turned what was once an important source of income into an expense for working artists.

Yes, marginal, new, and unsuccessful artists have long been precarious. But Silicon Valley’s implementation of a business model earning itself hundreds of billions via the ad based exploitation of copyright infringing work has marginalized an increasingly large number of working “content creators”, driving many into substandard housing, work spaces, and multiple jobs; and out of health insurance, safe housing, and sleep.

The geographically marginal location of the GhostShip lofts— in Oakland’s industrial zone, far from the nightlife centers of SF, is not only a metaphor, but a sign and

symptom of a wider and deeper phenomenon: the economic marginalization of working artists.

The GhostShip’s Oakland location — right across the Bay from the SV corporations which drove them into fatal precarity — is also more than metaphor. These artists were driven out of less precarious situations by rent increases. San Franscisco real estate has gone through the ceiling as a direct result of the huge wealth of Silicon Valley corporate execs, investors, financiers, and employees.

Rage at this Silicon Valley driven gentrification has been local news for almost a decade. Conflict between local residents and SV employees broke into violence over Google’s usage of public bus stops for their private busses. Leftists may not consider the local residents’ choice of an epithet (“dot.communist”) the ideal metaphor for evil, but it was meant to express the contempt Bay Area residents felt for the tech industry yuppies who drove them out of their homes and work places.

Working artists were by no means the only San Franciscans displaced. But added to the injury of artist displacement was the insulting knowledge that the money enabling their displacers had been generated by their own labor, expropriated via ad based profits on infringing files of their own work, files often posted and used without their consent or remuneration.

Silicon Valley propaganda outlets like the Google funded “Electronic Frontier Foundation” have long taken the position that the 60% collapse of the record industry caused by infringement was only hurting rich major record company exec’s, that somehow you could suck 7 billion a year out of an industry without hurting the working artists — and engineers, and indie label staff, and photographers/graphic artists/designers etc — who worked with them and lived off the sales of their music.

So now the precarity caused by these policies has hurt real people. And the only thing unusual about those hurt or killed in the GhostShip fire was that, unlike the hundreds of thousands of individual, isolated disasters caused by structural precarity, this hurt made national headlines.

Our personal disasters —the broken relationships of those working two jobs, or forced onto the road because that’s all that’s left, the deferment or avoidance of family due to poverty….the dislocations, evictions, foreclosures — will never be on CNN or Fox News. But we all know people, or are people, who have suffered them.

“Precarity” describes the social dimension of supposedly “natural” disasters: the increased risk of death, injury, and misery for those pushed to the social edge. The cause of death may be attributed to natural phenomena: fire, flood, earthquake. But the degree of risk is created

socially: politically, legally, economically. San Fransisco’s “Loma Prieta” earthquake of 1989 registered 6.9 on the richter scale and resulted in 63 deaths. The 2010 Haitian earthquake was a similar magnitude (7.0), but resulted in over 160,000 deaths. The earthquake didn’t kill: substandard housing did. It’s poverty, not nature, that places people in substandard housing. And it’s the lack of political rights and power that condemn populations to poverty.

The precarity pushing ‘content creators” to the social edge is entirely political, caused not by digital technology itself, but by:

1. the special privilege “Safe Harbor” clauses of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1997-98, which prevent artists from seeking damages from online corporations, even those, like YouTube, whose business model is based on the mass infringement of artists rights.

2. The 2ndary boycott provision of the Taft Hartley law which limits the target of “collective economic (ie: union) action” to the immediate direct employer (meaning that almost all corporate profiteering from ‘content’ is off limits to labor action by almost all producers of content).

Many people know that Taylor Swift withdrew her material from Spotify to protest its low rates of pay. Fewer

know that if Ms. Swift had asked other artists to join her, or the public to boycott, she could have been sued for everything she ever made or ever will make. And if a union had made that call on her behalf, they could have seen all their assets, including pension funds, seized, and their officers arrested and placed under gag order.

3. Reagan era court decisions limiting the scope of anti-trust law, even when corporations are clearly using their “monopsony” power to crush producers.

Rip, Mix, Burn

The february 2003 edition of Wired Magazine celebrated the death of the recording industry with a cover (referring to Charles C Mann’s accompanying “The Year The Music Dies” article) consisting of a famous graphic image of the Hindenburg disaster, in which hundreds of passengers were burnt to death in the ill-fated zepellin’s launching.*

This graphic image was accompanied by the text “Rip, Mix, Burn”, a slogan borrowed from an Apple campaign to both advertise their product as a tool for copyright infringement and rationalize the harm done to artists by presenting a for profit corporate campaign as anti-corporate direct action. Apple profited greatly from sales to consumers using their product precisely as suggested.

Wired’s advertisers are often tech corporations reaping similar profits.

The clear implication of Wired’s gleeful use of the Hindenberg disaster photo… is now obscene.

We now know that “the music” didn’t die in 2003. Musicians still make music (using similar technological tools to those in use since the 90’s). People still listen to the music musicians make. Their listening is still mediated by corporations, and still produces (now more than ever) profits for those corporations. Only now those profits aren’t shared by the people who produce them. This isn’t ‘creative destruction’, or ‘technological unemployment’: its exploitation pure and simple.

Thanks to the Safe Harbor clause of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, and the 2ndary boycott provision of the Taft Hartley Law, content creators have been prevented from fighting this exploitation individually and collectively.

Denied legal means of fighting back, politically swamped by the massive lobbying power and social media manipulation of Silicon Valley corporations, artists have been pushed into economic precarity and risk.

As is so often the case with the violation of rights, violence against the body is the inevitable consequence.

M. Ribot

The author is a member of NYC artists rights group MusiciansACTION http://musiciansaction.org/.