In this piece, Thomas Euler ponders the question of why it is that we can still purchase music. Will we soon live in a world where music cannot be bought. but only accessed, and what this would mean for not only labels but also the industry in general?

_________________________

Guest post by Thomas Euler, originally published on his blog attentionecono.me

We are witnessing one of the most interesting power struggles between major players from the old and the new, digital world. Plus, the industry is a great case study into the business models which define each world - and into the dynamics of that transition.

To that end, I asked myself the following question: Why can we still buy music? Depending on where you’re coming from, the idea that we could one day be living in a world where music cannot be bought but only accessed, might sound either crazy or consequential. I think it’s reasonable to ask.

From Bill Rosenblatt on Forbes:

For over 20 years, people have envisioned a future in which you don’t need to own music, where a vast library music is available everywhere from a “celestial jukebox.” Although that vision became reality several years ago through services like Spotify, today it’s more than a vision: it’s the majority of the music industry. The most recent data shows that listeners get more music, and the industry makes more money from it, through “access” models than through “ownership.” This is a major tipping point in music’s digital transformation, and it’s happening now.

The RIAA publishes detailed summaries of recorded music revenue by sourcetwice a year. The 2016 annual numbers brought some good news for the music industry — that it has returned to growth after five years of stagnation. But more importantly, streaming services are now the majority source of recorded music revenue, bigger than downloads, CDs and vinyl combined.

The largest chunk of that revenue comes from on-demand streaming services like Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music Unlimited and TIDAL, which let users pick the exact music they want to hear. In this crucial sense, they are directly comparable to “ownership” models, which include physical products as well as downloads.

Rosenblatt goes on to dig into the numbers. His finding is not surprising if your follow the music industry closely, but it’s interesting nonetheless: The access model — the term summarizes streaming and radio — is about to take over the ownership model (physical + downloads) in terms of the label’s revenue from recorded music. That holds true even if you exclude free, ad-supported access from the equation. Consumers are willing to pay for access to music.

______________________________

Slowly but surely, music is turning into a service.

That’s hardly news. But most analysis is missing one key notion: A world in which music isn’t bought but subscribed to, is awesome if you own the music. Even back when people had to buy music, the average consumer spent way less on music every year than even a discounted yearly subscription costs these days. Plus, fans can never cancel their subscription — it would cost them their entire collection. Labels ought to love this.

From a business model perspective, established rights holders in content- and rights-based industries are incentivized to push for subscription models: Customer lifetime value is much bigger if you sell access instead of copies. The popular counterargument: It’s even better if customers do both. That is only somewhat true. Yes, there is a typology of customers who pay for a streaming service and buy (some) music.

Yet: The sheer fact that buying remains an option for everybody else, allows casual fans to only purchase music every once in a while. That’s precisely what most people do today: globally, streaming services have 100-something million subscribers. More people than that listen to music. Everybody who likes music enough to pay for it, but opts for the occasional purchase instead of streaming, is a lost subscriber.

Why then, one wonders, aren’t the labels pushing hard to establish the clearly superior business model?

For several reasons (with varying degrees of validity):

Consumer preferences: A decent chunk of today’s music fans is used to the ownership model. While sales in most categories decline (vinyl is growing), there is still a sizable amount of customers, particularly among the most dedicated fans, who prefer to own music (also, streaming isn’t beloved by all of them). Changing habits is a fight against inertia — you’re in it for the long-run.

Prioritizing short-term profits: I recently talked to an indie music publisher from Munich about the question. He, rightfully, argued that as long as there are customers who are willing to buy music, they will be served. Taking your customers seriously is a good thing. That said, labels could force customers into streaming. After all, they want the music. If it were to exist only on streaming services, many would go there. Thus, another reading of the publisher’s statement is: The industry isn’t willing to forego short-term profits for the sake of the better long-term business model.

Balance of power: While the labels own the most important asset in music, the catalogue, streaming services own the user. If you are a label, relying too heavily on Spotify, Apple Music & Co. creates a risk. As I’ve written before:

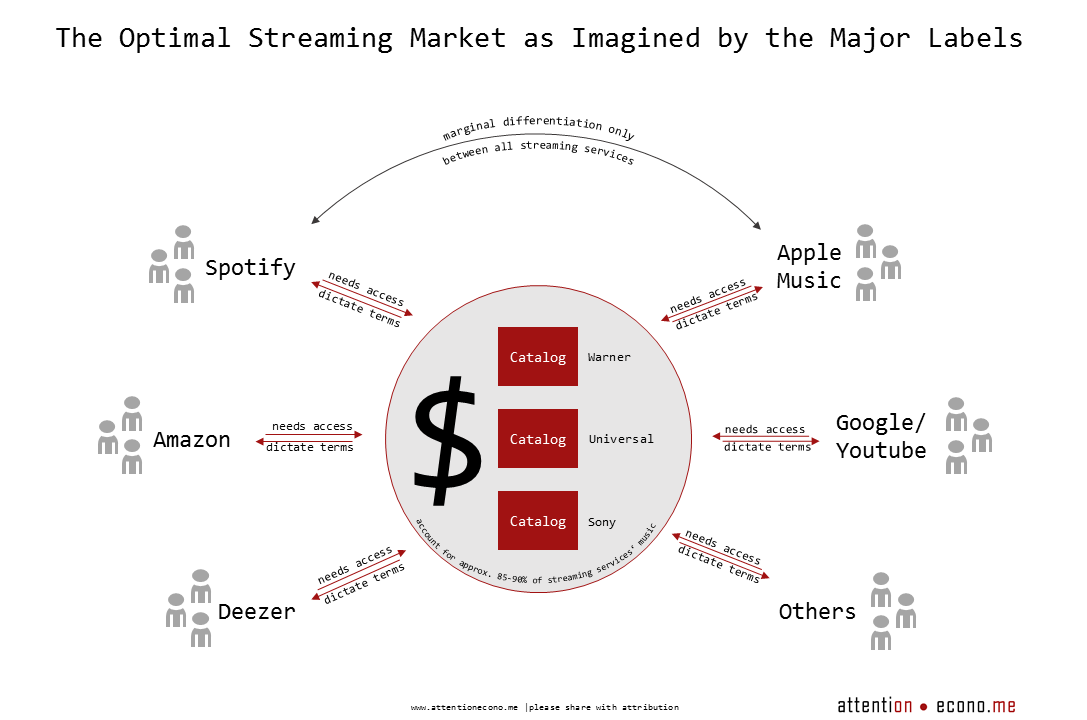

All the moves of the past years indicate that the optimal streaming scenario from the major labels’ perspective looks somewhat like this:

That translates to: A bunch of streaming services which are hardly differentiated, each has a decent, none a dominant market share and all are reliant upon the labels’ catalogues (and goodwill). Optimal conditions for the reigning major labels indeed.

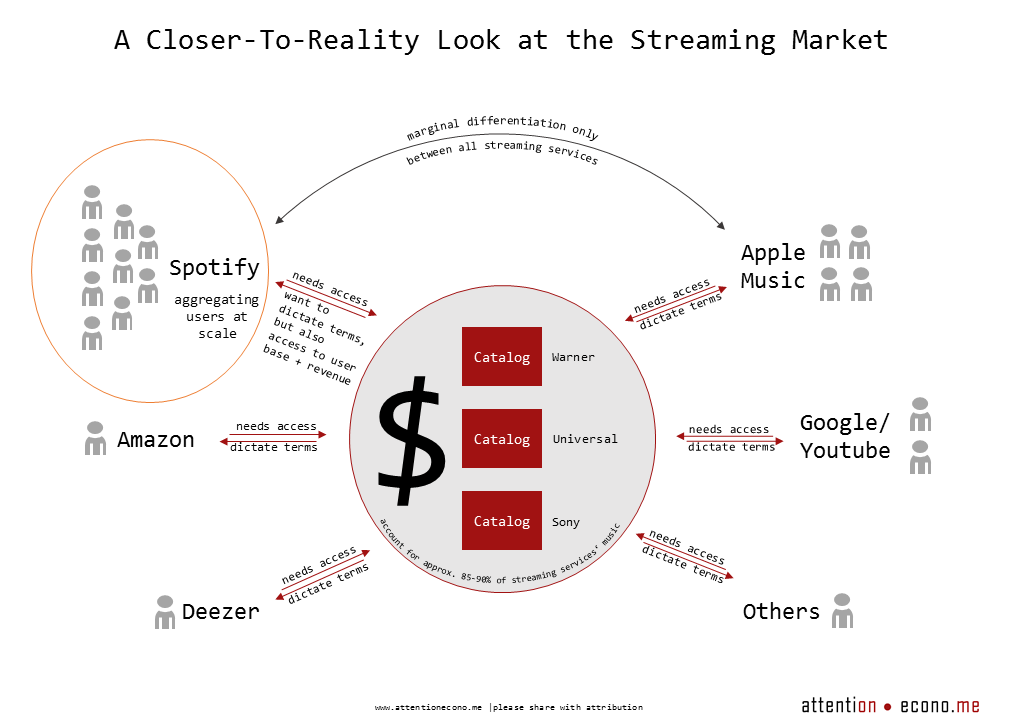

However, reality doesn’t quite look like the above graphic. It’s more like this:

The value of the labels’ catalogue derives from the fact that old releases matter in music. More so than in other media businesses. Still, having all distribution power in the hands of a few streaming services opens the door for them to do the Netflix. That is: Starting to build your own catalogue.

Direct-to-consumer artists: As I have stated before, I think the biggest structural thread for labels are artists who choose the DIY path, keep all their rights and publish their work on their own (or with help from smaller service providers). Streaming (and Bandcamp) are essential to this development. Their existence paves the way for a direct-to-consumer approach that is threatening the labels’ entire business model.

Organizational inertia: The labels succeeded, in large part, thanks to their distribution prowess. They basically used to be essential for artists. Both is no longer true in the streaming world. Pushing for music-as-a-service would require to let go of old believes and assumptions. Sometimes, that’s the hardest part.

All those arguments have one thing in common. They are all bound to time. They are a reflection of the world and the industry structures in place right now. None changes the fact that music-as-a-service is, fundamentally, the best business model for music rights holders. But make no mistake: disregarding time and reality would be wrong. It takes time for innovation to become the status-quo. Particularly when the innovation comes with a new business model and threatens powerful incumbents.¹

The reason we can still buy music, then, isn’t that the music-as-a-service business model isn’t superior. Instead, there is too much conflict-of-interest among all the different actors. For that very same reason, though, I’m rather confident we’ll get to a music-as-a-service world eventually. It just makes too much business sense. But it’s a process, and the transition period might even last a generation.²

That comes with a different implication: We can’t know who is going to be in the strongest position if and when the scenario manifests. It’s just as reasonable to assume that the major labels will continue to leverage their assets and maintain their position, as it is to think anybody from streaming services, entrepreneurial artists or some yet unknown actors will emerge as music’s leading force. The general direction, however, is way less fuzzy: a world where music is accessed, not purchased.

As I already put my forecaster hat on, let me add the one exception from the service model that I expect to see. It comes with a glimmer of hope for any fan who read all this with wet eyes. One day, you might no longer be able to buy files and CD’s. But the indie publisher I talked to certainly had a point: If people truly want to buy music, they will be given the option. For many people around the world, music is a collectible. Something they love so much, they need to have it. Physically.

Collectors, the real hardcore fans, have the highest willingness-to-spend on music. Plus, they know streaming just isn’t the same (let me tell you, as I’m one of them: it’s true!). They will be catered for. So, even in that music-as-a-service future, I assume the vinyl³ market will still be around. Ironically then, music’s premium segment would be based on a technology invented in the 19th century. Good things tend to last.