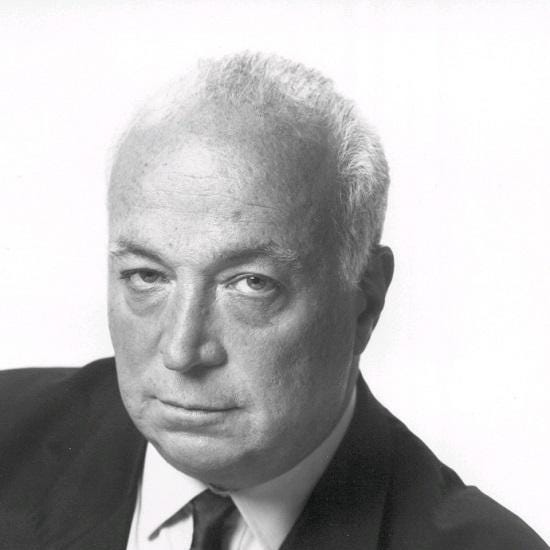

In this piece, soon to be 73-year-old music business legend and discoverer of Talking Heads as well The Ramones opens up with marked frankness about his groundbreaking career, as well as an embarassing deal made with Madonna.

______________________________

Guest Post by Yael Chiara on Medium

Seymour Stein, a bona fide music industry legend, turns 73 this month. Get him talking about music he loves, though, and he’ll match the passion of any young industry whippersnapper pound for pound.

Stein is still every bit as full as admiration for great bands as he was more than half a century ago, when in 1966 he co-founded Sire Records with his friend Richard Gottier. Through Sire, he played a vital role in bringing the likes of Talking Heads, The Ramones, The Cure, Ice-T and Echo & The Bunnymen to mainstream recognition.

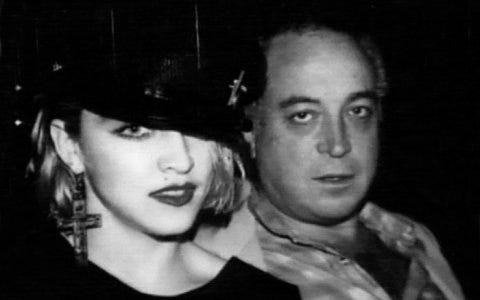

And then there was that signing, when Stein fell head over heels for the music and theatricality of Madonna Louise Ciccone — launching the career, in 1982, of a woman who would go on to define music’s pop culture time and time again.

These days Stein plies his A&R trade within the walls of Warner Music Group, and he remains a hero to the ‘next generation’ of independent music executives—those now running labels and publishers around the world.

[PIAS] founder Kenny Gates shared a coffee and a chat with Seymour at SXSW to delve deep into the career history of one of independent music’s true godfathers.

Kenny Gates: I’m sure you’ve told this story hundreds of times, but please do cast your mind back again: you started Sire in 1966?

Seymour Stein: Yes, late 1966 as a production company. If you go back a few years further, you find the reason we were able to get Sire started: I was 14-years-old, and the first man I ever worked for was Tom Noonan, the charts editor at Billboard magazine. He had just taken over a position at Columbia Records, running a label called Date. He helped Richard and I get a big advance — in those days it was a big advance, anyway!

Do you remember how much it was for?

Oh, of course. $50,000. It was a lot of money back then. Plus, we got free use of the Columbia studios anywhere in the world and [then] they would pay to sign up the acts. The $50,000 was just operating capital, which we desperately needed.

How did you and Richard meet?

That’s important! We met in the Brill building; that was my last job [before Sire] — working for Red Bird Records, for George Goldner, another one of my mentors. And in-between, after Billboard and after Red Bird, I worked for King Records. Syd Nathan at King was my greatest mentor. [King’s roster included] James Brown, Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, Freddy King, and a great country roster. I know that without being mentored by these and other people — including Ahmet [Ertegun] and Jerry Wexler, even Nesuhi Ertegün — I wouldn’t have had such a successful career. I believe in mentoring very much.

Well you are one of my mentors! I’m amazed by your longevity and your passion.

Thank you — I’m amazed at it too given the life I’ve lived!

How old were you when you started Sire?

I was, let’s see, 22. But Sire wasn’t a label to start with; it took about a year-and-a-half for that to happen. Again, I was very fortunate. We had no office. Syd Nathan was closing down the King headquarters in New York and rented me this amazing office for $325 a month. The first thing I did was to take the biggest room in the office and rent it out to Julie and Roy Rifkind — Roy was a manager and Julie was a great record man, working for Bang Records. Bert [Berns, Bang co-founder] did all the producing and Julie did just about everything else.

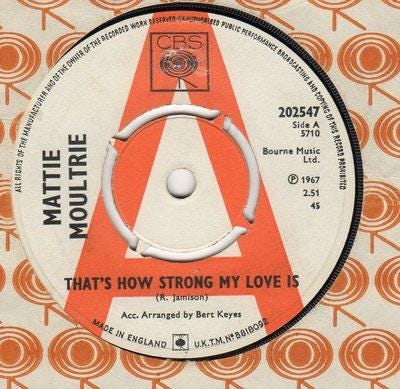

What was the first artist you signed?

It was a woman named Mattie Moultrie. She was a black woman from Georgia, and I had always loved that song — “That’s How Strong My Love Is.” That was the first thing we did with her. Columbia wanted us, as much as possible, to sign black acts. They stated that. My background with King meant I used to go on the road with James Brown, amongst other things, all in my late teens. I never went to college.

They also had this guy Dave Kapralik at Sony who brought in Sly & The Family Stone — when they finally ‘got’ it. The majors lagged behind [the indies] and even within the majors, Columbia lagged behind Decca, Capitol and RCA in terms of getting involved in rock & roll, rhythm & blues… Part of the reason they did the deal with us was to play catch-up a little bit.

You say you didn’t go to college. Did your parents support your business career?

They didn’t understand it. My father just scratched his head. But they didn’t interfere, and that was help enough. My father was an orthodox Jew, so, you know. He didn’t believe rock & roll was the devil’s music or anything; in fact, my father loved music. He told me about his days of checking out vaudeville shows.

And your mother wasn’t scared about the music industry?

No. My mother came from a totally different background. She’s Jewish as well, but my grandparents were in the Italian food business. So I think my mother was a little more rough and ready! I loved music ever since I was a boy. My sister is six years older than me, so I heard pop music very early.

So your sister is responsible for getting you into music?

Well, I just listened to the radio with her. She had records. It certainly helped me in life to have a big sister, yes.

Was there a defining moment from your teens when you thought: ‘I’m going to be successful in this business.’

I wanted to be part of the music business since I was nine years old. I went up to Billboard when I was 13 to do research on the charts. Tom Noonan was very gracious and gave me access. I’d go there every day after school — my parents didn’t like that, but then they met Tom.

Was there a moment where your parents saw that you were successful?They both lived to see Madonna be №1 on the charts. They were very proud of me.

You’re twenty years older than I am — I see you at shows, underground gigs, terrible toilet venues. These are places no sane person would want to go!

Well if I survived the toilet at CBGB’s, which didn’t even have a door, I think I can survive any toilet out there.

What gets you up in the morning?

I love to work. I think it keeps me young — at least in spirit and in mind. I mean, what else would I do? It offers me so much. 15 years ago, when music really started to taper off [through piracy]. I was low. I felt everybody, if they want to, should have the experience of being in the business. And I knew that if there wasn’t a music business, it would be terrible.

How did you stay positive about the business during that period?

I started focusing on India and China, which I still do. 20–25 years from now, I probably won’t be around, but over 80% of the world’s population will be in Asia and Africa. It’s hard to believe. I remember when Hong Kong was totally a pirate market. Nothing is impossible. There are 1.3 billion people in China. And in India, there’s 1.2 billion, but it will eventually be bigger than China because there’s no restriction on the number of children they can have. In each of these countries you have 400 million or more middle class people—with millions more joining the ranks every year. [The music business] really better get started in these markets.

You’ve been internationally-minded for a very long time, though.

Great hits can come from anywhere. I put out Australian music in America before anyone — a record “I’m Stranded” by The Saints. I felt bad, I heard this record in EMI and they said, ‘Oh, you can have this. American record labels will never put this record out.’

Well, why should they? They rejected The Beatles twice — not once, twice! That’s why those early [Beatles] records came out on a rhythm and blues label, Vee Jay. And when Vee Jay couldn’t pay royalties, the rights came back to Capitol. And then Capitol rejected them again! That’s why Swan Records put out “Please Please Me” [in the U.S.].

I told The Saints’ manager that I’d never signed a band until I’d seen them live, and that I’d always wanted to go to Australia. Eight months later, I went out there and signed [The Saints] and another band, Radio Birdman. Both of those bands have been inducted into the Australian music Hall Of Fame, and I’m very proud of that. You, of course, know of the success I had in Belgium with “Ca Plane Pour Moi” [by Plastic Bertrand] and with Telex. In fact my first million-seller was Focus, “Hocus Pocus” from Holland.

When you signed Madonna, did you think she’d still be making music 30 years later?

I didn’t think about it. What people usually ask me is, Do you think she’d ever be this big? Of course not! I knew she was special.

And you met her through Mark Kamins?

Yes, I’d always befriended Mark. He was a DJ who played all sorts of weird music but somehow made it work — he was playing Faro music, mixing it with African music and making it all work. I gave him $18,000 and I told him: ‘This should be enough for you, over a period of a year or longer — don’t rush it — to make six demos.’ Madonna was the third demo he brought me. I listened to it, and I loved it.

Everyone knows this story: I heard it in the hospital, and I got so excited, I made her come to see me. No, that’s not true — even then you couldn’t make Madonna do anything unless she wanted to! She came to the hospital and we agreed on a deal right then and there. I asked her to go to her lawyers so we could draw up the papers.

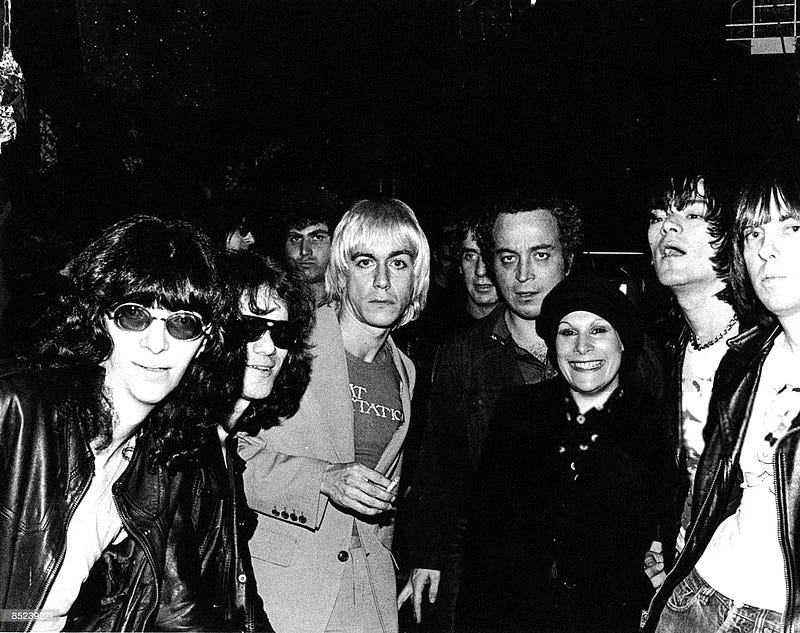

All these bands you signed: Talking Heads, The Pretenders, The Ramones… Discovering The Ramones must have been an incredible moment.

Yes, but a regrettable moment in a way. They’re all dead now—the last of them died last year. In addition, they never sold [what they deserved to]. But they influenced so much of the music business. I met with someone from The Grammys recently, and they’re going to do a big spotlight on The Ramones next year.

It breaks my heart they weren’t bigger. But whenever the public learn who I am, the first thing they ask about is The Ramones. So they have ‘made it,’ I suppose, it’s just horrible they’re not alive.

To me and many others, you are a friend of the indies, but you work for Warner. You are the most independent major label executive!

Yes. Well, first of all, Warner is a bit different than the other majors. It never started out to be a major label. Warner started out the way the other record labels did — in the motion pictures business. Columbia Pictures had a label — all of them did. But luckily, they bought Reprise Records, and with it they got a business man who was very smart in Mo Ostin.

Then they bought Atlantic, which was the greatest of all the indie labels. They actually paid their artists — that’s how great they were! I’m not saying the others didn’t, but Atlantic was the most honest. They started Bang: it stands for Bert, Ahmet, Nesuhi and Jerry. And they bought Elektra Records—with that they got not only a great music man, but a great technical guy who knew about making records: Jac Holzman. Jac still works for Warner to this day. When I got inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, I was embarrassed that I was inducted before him. Such a great music man, you’d love him. Like me, like you, Jac’s an independent.

It sounds like I’d like him. You still consider yourself an independent executive?

Of course! It’s in my blood! I don’t think like a major label. I’ve never gone after a big artist. Lou Reed came to me because his lawyer recommended me after he left RCA. I’ve never done any big deals. I’m embarrassed to tell you what the deal was with Madonna. She’s probably a billionaire now! I’m very happy for her, and very proud of her.

You said you were embarrassed by the deal: you have to tell me!

$15,000 for three singles and then an option to pick up an album. That was not the usual kind of deal, but I felt that she would be the queen of the 12-inch — and she was. And when I heard the fourth single, “Borderline,” I knew there’d be no stopping her. I always believed she’d be very big, but not like she became. I couldn’t even think that big!

When you sign an artist, is it the song or the performance that makes a difference?

In almost every case, it’s the song. Recorded music is about 150 years old. But there’s been a music business for hundreds of years. Warner/Chappell is 215 years old, and Schott Music in Germany is even older than that. There’s no such thing as ‘classical music’ at birth. Bach, Beethoven, Mozart and people like that were rock stars! Because they survived, they became ‘classical.’ I’m sure Elvis will be considered ‘classical’ at some point, same with Madonna.

What’s your greatest miss? Which one band do you most regret not signing?

Oh, there are a number of them. But I’ve signed so many, successful and unsuccessful, that I’d rather not dwell on it.

Would you consider yourself a hopeless romantic?

Well I am hopeless, so at least half of it is true [laughs]. I just love what I do. I don’t have to work, but I don’t know what else I’d do if I didn’t. If and when the time comes that I’m really not able to do this, and I’m still trying, I hope someone’s good enough to sit me down and say: You know, enough is enough. But I don’t feel that time has come and I’d like to keep going.

Is it true you had a complex about being a musician, then found out it was better not to be one?

Yes, it’s true. I was at the Windsor Pop & Jazz Festival in 1966 or 1967. Jethro Tull were playing and they were unsigned. Mike Vernon was a producer then. I said to him: ‘Look, this band are great.’ And he said to me: ‘Oh Seymour. I could never work with a flautist.’ I didn’t know what a flautist was — we called them flute players! I thought he meant he was a deviant or something.

So I turned to Gus Sturgeon, who was sitting to the other side of me. He was an engineer who became Elton John’s producer, and I told him: ‘You could be involved in [Jethro Tull] — you could be their engineer.’ He said to me: ‘Seymour, obviously you don’t play a musical instrument. If you did, you’d have heard all the mistakes they made.’

What’s been the highest point and lowest point of your career?

All I can say is, I love the business so much — and I love being part of it so much. It’s been mostly high with a few lows. I’ll tell you what I’d like to leave behind a little bit—to make it a truly connected world of music, that’s why I’ve spent so much time in Asia.

Would you still recommend someone sets up a label in today’s music business market?

There are good times and there are bad times. There are opportunities during both. Music is not going away. The music business is older than the film business and certainly older than radio or television. I don’t know of any form of entertainment, other than live theatre, that’s older than music.

A kid on the street knows more about the technology than I do, so I guess I’m no good in that regard. But the one thing that’s the constant is that it all begins with a song. Great music, for the most part, will always prevail — sooner or later.

You mentioned before we sat down that you have a book coming?

Well, I have to write it first! It’s true that I’ve got the deal in place. I’ve probably given half of it away in this interview!

Find out more about The Independent Echo, a blog from [PIAS]—the independent music powerhouse, celebrating the character, knowledge and history of the independent music business