While the latest news from the music industry certainly seems positive, with eight percent growth in revenues courtesy of streaming, for those who look more closely there may also be some concerning indicators hidden within those numbers.

________________________________

Guest Post by Jon Maples

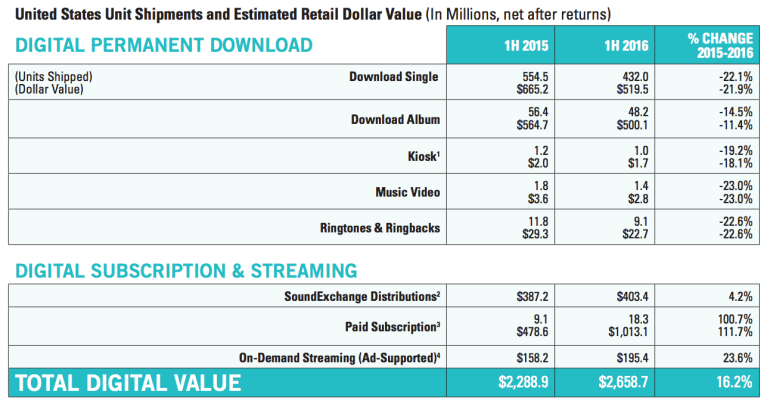

News this week, for once, was positive for the music business. The RIAA released its report for the first half of this year and there was an eight percent growth in revenues over the same time 2015, thanks to subscription streaming. At long last, after years and years of losses, we’re finally on the other side of the decline and now we’re going to see a huge run up of revenues as the industry continues to grow like gangbusters. At least that’s what you’d think from the headlines. I agree: it’s a good result. But there are also troubling signs in the numbers.

Source: Recording Industry Association of America

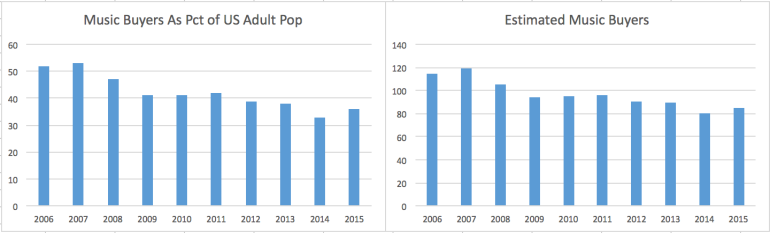

You see, while revenues are up, the number of people who buy music has steadily fallen for the past decade. According to MusicWatch, a music industry research firm, the number of people buying rebounded a bit in 2015 to 85 million, it’s still significantly down from the buying population 10 years previous.

Not all consumers are created equally. Over the years the average consumer spent around $50 a year on music. Sounds pretty good, right? Well, the average consumer only about about 1.5 CDs a year. So how is that possible. Well, there was small number of consumers who bought 10 or 20 times what most consumers did. I used to see this all the time in line at my local record store. I’d be wondering if I should be buying the 10 CDs in my hand on my meager first job salary (the answer was no). Meanwhile, the woman in front of me was buying the Debbie Gibson CD for her daughter. It most likely was the only CD she’d buy all year.

-

- Sources: MusicWatch and U.S. Census Bureau Music Buyers in Millions

This has all changed in the subscription era. We’ve flattened that curve between the casual buyer, who only bought Adele’s 25 last year, and that obsessive-compulsive music nut who happily subscribes to Spotify. Sure, the nut is still spending much more than casual fan. But at $10 a month, it’s capped at $120. And yes, the music nut might also purchase vinyl, buy up posters at Flatstock, and attend music festivals, but they don’t have to pay more for all that music. Many super fans I interviewed to while working at a streaming service thought they were getting away with something by only paying $10 a month.

The theory of the streaming era is that we’ll produce so many more subscribers, that we’ll make up the difference in revenue. But thinking that casual fan will pay twice as much as the average consumer spends is fairly flawed logic.

Especially when one considers how people are listening today.

Based on MusicWatch’s recent audiocensus report, more than 70% of all listening today is on services that are free, like Pandora, YouTube, Spotify’s free service and iHeartRadio. Because when faced with the choice of $10 a month for something they use rarely or free, casual fans choose free. Duh. Hence the massive decrease in the percentage of buyers.

Much like how the U.S. economy recovered in the years after the housing market collapse, but only with many fewer jobs, the music industry is recovering. But with many fewer customers. And the pain is just coming. Compact discs may only be a shadow of its former self, but there were still 38 million CDs shipped in the first half of this year. Question: when was the last year you bought a device that can even play a CD? While vinyl and even downloads have a purpose and will maintain some attractiveness, my contention is that CDs will go to zero. This, my friends, is a problem.

So what can be done?

Perhaps address the product itself. Streaming services main use case is access to all the music. While it’s great for the fan that knows what she or he wants to play, it causes more problem than it solves for the casual fan. After all, how many times do you sit at your computer and not know what to play next. Even with 30 million songs only a seconds from a search.

Considering after all these years peddling subscriptions to consumers, we now have a total of 18 million subscribers in the U.S., I’m sure it’s safe to say that the $10 all you can eat music subscription isn’t the product for anything but the super fan. Will there be more growth? Yeah, sure, no doubt. Can it grow to 50 million? Doubtful.

So what about lowering the price, which has been bandied about as a cure all? Beyond the fact that rights holders won’t budge on price, it probably is the wrong product for those who like to listen occasionally. “Casual fans have different needs than super fans and may be fine with a more basic experience,” Russ Crupnick, managing partner of MusicWatch, told me via email. “So converting them to paid requires a different set of strategies and tactics. Lowering price alone won’t automatically convert them into super fans.”

Last week Pandora announced improvements to its free service as well as Pandora Plus, a product that merges a few on demand features, like more skips and the ability to save tracks to the phone for offline use, to its core experience. Can the new product as well as Amazon’s planned subscription service, which apparently will share Pandora Plus’s $5 price, help? Perhaps.

But those are just two ideas. In the world of product development, it takes many attempts to find the perfect product market fit that people are willing to pay for. Licensing two and saying ‘okay, we’re done,’ is not going to cut it. It took 15 years, a handful of flopped companies and at least a couple hundred million in funding before AYCE streaming services finally produced a billion dollars in revenue. My guess is that it will take years to attract the casual fan. Fact is, we’re going to need wave after wave of ideas to grow customers again.