Although some may now consider it an antiquated medium, tape and experimentation with tape played an important role in development of recorded sound. Here we look at five important moments from the history of tape.

__________________________

Guest post by Leticia Trandafir of Soundfly‘s Flypaper

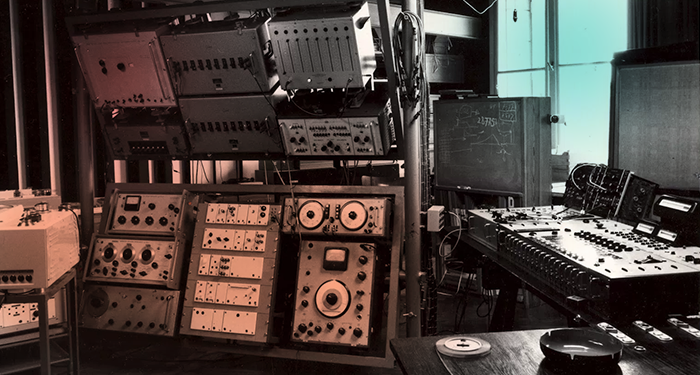

Before the synthesizer, electronic experimenters were already at work with another instrument – the tape recorder.

Before the ability to record, musical excellence, virtuosity, and authenticity were associated with playing a live instrument. In fact, recording was often perceived as a “dishonest” activity by some artists at its introduction. Until it fell into the hands of those willing to experiment…

Of course, magnetic tape isn’t the first recording medium — we had paper or wax cylinders and vinyl discs before. But magnetic tape had an excellent frequency response, it was cheap, and you could easily cut and splice it. In other words, it was a tweaker’s paradise.

The ability to record and especially manipulate sounds was a completely new concept that tape unlocked. You could take music out of its time and place, hear it again, cut it up, and rework it into something else. The tape recorder was turned on its head and became an instrument.

In the big picture of music it was the beginning of a whole new era of creativity — we’re still feeling the effects right now. Here are five key moments in the history of tape music that changed the way we make music today.

1. The First Electronic Music Composition

“The cradle of electronica is Cairo” – wrote Rob Young in The Wire.

Many have crowned Pierre Schaeffer as the originator of electronic music. But the world’s first electronic composition is actually “Ta’abir Al-Zaar,” made in 1944 by the Egyptian experimenter Halim El-Dabh.

El-Dabh used a wire recorder to capture zaar, a women’s healing ceremony featuring drums, flutes, and singing. He returned to the Middle East Radio station and used echo and reverb chambers to manipulate the timbres. He isolated, enhanced, and removed certain frequencies.

He then transferred his composition onto a reel-to-reel, edited the composition, and renamed it “Ta’abir Al-Zaar” — The Expression of Zaar. The original piece was not preserved, but a two-minute excerpt appeared on CD under the title “Wire Recorder Piece.”

El-Dabh is most known for his experiments in the US during the 1960s at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, the oldest center for electronic music research in the United States. He was briefly Igor Stravinsky’s assistant and worked alongside folks like John Cage, Vladimir Ussachevsky, and Otto Luening.

2. “Tape Music An Historic Concert”

Vladimir Ussachevsky and Otto Luening are among the first American composers to integrate tape music into live performance and recordings in the United States. In 1952, Luening and Ussachevsky presented the first concert of music for tape in the US at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The result was pressed onto vinyl in 1968 and entitled Tape Music An Historic Concert.

What was so striking about this concert? It showcased the creative capabilities of tape in conjunction with classical instruments — distortions, superimpositions, echoes, and timbral transformations fused with an orchestral composition.

The result was an eerie and completely new kind of sound for the time. It marked the beginning of an American chapter in the legacy of tape music already happening in France, Britain, and other parts of the world. The famous conductor Leopold Stokowski, who went to the show, described tape music as:

“Music that is composed directly with sound instead of first being written on paper and later made to sound. Just as the painter paints [their] picture directly with colors, so the musician composes [their] music directly with tone…”

In the late 1950s, Ussachevsky and Luening founded the seminal Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center.

3. Pierre Schaeffer and Musique Concrète

Founded in 1951, the Groupe de Recherches Musciales (GRM) was a studio based out of the Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (RTF) headquarters in Paris. The GRM is the historic electro-acoustic music group founded by composers Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry and engineer Jacques Poullin.

This studio allowed Pierre Schaeffer to continue developing his theory of musique concrète: a music that used recorded sounds as base material for composing. Shaeffer encouraged acousmatic listening — listening to sounds for their acoustic and rhythmic qualities without knowing or trying to know what causes them. Tape played a fundamental role as a medium for recording and manipulating those experiments.

The techniques developed by Shaeffer for editing sounds laid the foundations for sampling and the computer music approach we all use today, specifically altering the pitch, reversing a recording, cutting, and filtering, to name a few.

Musique concrète was among the first movements to add recorded and electronic sounds into the composer’s toolset. It was a precursor to electronically generated sound, but the techniques still resonate today in electronic music production.

4. Pauline Oliveros and the Tape Music Center

Around the same time in late ’50s, the Tape Music Center was co-founded in San Francisco by avant-garde composer and accordionist Pauline Oliveros.

Oliveros adopted a different approach to composing:

“While everybody else was cutting and splicing materials, I was finding a way to improvise with the electronics. That improvisation system was using difference tones between oscillators. Setting oscillators above the range of hearing and using the difference tones between the oscillators in a tape delay system caused a lot of beat frequencies with the bias of the tape recorder. That’s how I made my early electronic music.”

Oliveros started pioneering live performance techniques with tape machines. She used large tape recorders with big reels. The supply reel would run through one deck to another, sometimes even a third. All the tape decks would record and feed the recording into the next and back into the first.

She did not use loops; she left the tape running for as much time as it had. In Oliveros’ hands, the tape recorder became a performance instrument, going beyond just a recording device. This set the tone for a long tradition of misusing recording equipment and reinventing them. She compiled her techniques in the 1969 essay, “Tape Delay Techniques for Electronic Music Composition.”

5. Delia Derbyshire and the BBC Radiophonic Workshop

Delia Derbyshire started working at London’s BBC Radiophonic Workshop in 1962. Derbyshire used the Workshop as a playground for her innovative ideas. She utilized musique concrète techniques that used found sound — like a plucked string as the starting point for a bassline alongside sine tones and white noise carved, filtered, and shaped.

Her most famous work is the theme song for the kids’ show Doctor Who, one of the first television themes to be made entirely with electronics.

Every note has to be created as a separate piece of tape. Each piece was then cut together to create the rhythm and the melodies. There was no multi-tracking at that point, so the final mix was done by playing back the various pieces of tape together and hoping it would stay in sync from start to end.

“This century, the technology has caught up with Delia. We can now do digitally what Delia was doing in analog terms. Delia would be having a bore now” – asserts Mark Ayres in The Delian Mode documentary.

We Owe It to Tape

The style of music coming out of the BBC Radiophonic workshop, the Tape Music Center, the GRM, and others of that period created an aesthetic and technical legacy that inspired generations of upcoming artists. It laid the foundation for how we all create music today.

The well-known German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen commented on the importance of tape:

“This is the most important: For the first time in history, we have the possibility to make the sound become fixed for a while and work on it. Traditionally, sound was constantly moving. Once it was produced, it was gone.”

Tape is the the technology that gave us recording, sampling, looping, delay. So, the next time tape seems obsolete in the days of digital, don’t forget that its histories loop back into modern music every day.

To learn about modern mixing techniques (like EQ, Compression, Level, Pan Setting, Digital Signal Processing, FX Sends, and so much more) from some of today’s leading sound engineers, preview Soundfly’s newest and most in-depth mentorship-assisted online mixing courses, Faders Up I & II: Modern Mix Techniques and Advanced Mix Techniques, for free today!

And right now, if you sign up for either course before January 31, you can take 30% off (that’s $150) with the exclusive code MIXINGMONTH.

Leticia Trandafir is a DJ and music maker with a love for 303 basslines. Writer and Community Manager at LANDR.