Stuart Dredge explores how the new hardware category of the smart speakers is transforming the music landscape and what the technology’s rise could mean for the future of music and the music industry.

_______________________________

Guest post by Stuart Dredge of Music Ally, originally appearing on Medium. Join Stuart and Music Ally at their Sandbox Summit NYC music-marketing conference in New York on 25 April

[This is an edited version of a speech I gave at the recent Everybody’s Talkin’ event organised by British music industry bodies the BPI and ERA, along with Music Ally (who I work for). You can also read my writeup of the event itself , and download the free PDF report that went with it.]

I want to start by looking back to a job I had a long time ago, in 2001, when I worked for a magazine called T3 writing about gadgets and consumer technology. One of those gadgets was Apple’s first iPod, which we were very excited about.

We shared an office with an audiophile hi-fi magazine, whose team were surely appalled at the sound quality of our compressed MP3 files. But we were just overjoyed about having our entire collections in our pocket, often on shuffle.

We didn’t know, at the time, what the iPod would mean for musicians and the music industry: from the unbundling of the album to the evolution of listening habits, to the corporate future of Apple, which was still early in its comeback.

So, there was a new device, but its long-term implications weren’t immediately apparent.

Fast forward to 2008, and the launch of Apple’s App Store, a year after the first iPhone. I was working for a mobile games website by then, and we were very excited about playing Super Monkey Ball on the train.

But lots of other people were just as excited about an app that let you pour a virtual pint, or an app that let you swish a virtual lightsaber — with the right noises.

But again, the long-term implications weren’t clear: we didn’t know that mobile games would become a lucrative industry driven by in-app purchases; nor did we know that smartphone apps would be the route to 71m subscribers for Spotify. Which, by the way, only launched commercially (and desktop-only) a couple of months after the App Store.

But still: new hardware (and in this case a digital store) came out, but it took time to understand what it would mean for consumer habits and for the music industry.

Fast forward again to November 2014, and Amazon’s low-key launch of its first Echo: a smart speaker, connected to the internet, controlled by your voice, with a built-in assistant called Alexa that could play music, answer questions, turn your lights on and off, and even tell you jokes.

It was later followed by Google Home and Apple HomePod, and maybe in the coming months they’ll be joined by speakers from Facebook and Spotify too.

Smart speakers are a new hardware category, and this does remind me of the iPod and the App Store in that we have some ideas about what these devices mean for music, but it’s very early and there will certainly be surprises ahead that we can’t predict.

I’ve spent the last few weeks writing a report in partnership with the BPI and ERA. It’s partly a primer on smart speakers — what they are and how many have been sold — and partly an attempt to ask and answer some of those music questions around them.

We’ve heard from Futuresource [at the event, they spoke before me]: it predicts more than four million smart speaker sales this year in the UK. Globally, some analysts think the total may be north of 56 million. So what does that mean for music?

What does it mean if you control music with your voice not a screen? What does it mean if you’re just asking Alexa, Google Assistant or Siri for ‘music’ or ‘party music’ rather than specific songs or albums?

What does it mean for Spotify that its three biggest streaming rivals are also the companies making the main smart speakers here in the west? These and other talking points came through in the research for our report.

First: these are not just devices for tech experts or hardcore music fans. This is an important point: most new technologies are marketed first at tech-savvy early adopters, and then later on they go mainstream.

But right from the start, smart speakers have almost leapfrogged that. It’s a cutting-edge technology — voice control, and intelligent assistants responding to your commands — but one that’s marketed to a really mainstream audience: Amazon’s customer base being the perfect example.

This is encouraging: these are the people who our industry wants to persuade to pay for a music-streaming subscription.

ERA stats suggest there were between 8.1 million and 8.3 million music subscribers in the UK at the start of this year. And in 2017, spending on those subscriptions grew by 41.9% to £577.1m.

That’s good news, but the task now is to keep that momentum going by making subscriptions as appealing and accessible to mainstream people as possible.

A recent study from NPR and Edison Research in the US found that 28% of smart speaker owners said that getting one of these devices had caused them to pay for a music-subscription service.

Smartphones are certainly one route to those people. Smart speakers are another: especially if, as on Amazon’s Echo, subscribing can be as simple as saying ‘Alexa, sign up for Amazon Music Unlimited’.

So when we think about where will the next 8.3 million British music subscribers come from, these speakers could have a big role to play.

Second: These devices may fuel a different kind of listening. I want to talk about casual listening — you could call it lean-back listening — where you’re not taking the driving seat for discovery.

It’s not you saying ‘play me the new Courtney Barnett single’ or ‘play me Skepta’s album’, but you sitting back and letting someone else choose the music that you hear.

This isn’t a brand new thing at all. It’s radio: you turn on 6Music or 1Xtra and the DJ plays you music. It’s also streaming playlists: you fire up Spotify’s Discover Weekly or RapCaviar playlist, or Apple Music’s Lads, Lads, Lads, Pints, Pints, Pints playlist.

(Which really is a thing that exists! I salute them for it…).

One thing we understand from Amazon and others is that smart speakers are encouraging this form of listening too.

One of the most popular voice commands is ‘Play me music’. But these devices are also training new kinds of query: like ‘play me upbeat indie music from the 1990s’ or ‘play me love songs’ or ‘play me party songs’, or ‘play me music for cooking’. And then out comes a stream of tracks.

One talking point here is who is deciding what comes out of that speaker? It’s increasingly a combination of humans and algorithms.

When I say ‘play me music for cooking’, it may be an algorithm picking an Italian cooking playlist that was originally compiled by a human.

Or when I say ‘play me party songs’ it may be that one algorithm has decided what’s a party song and what isn’t, while another algorithm has ingested all my past listening data to then decide what my kind of party song is.

If I ask for party music, my speaker might play me ‘Groove Is In The Heart’ by Deee-Lite. But my dad’s speaker might play him ‘Come On Eileen’ by Dexy’s Midnight Runners, and if my son had one, it might play him ‘Man’s Not Hot’ by Big Shaq. Which to be honest, is currently the right song for pretty much any request he might make.

The point here — besides those three tunes being the best start to an all-ages wedding reception — is that while we may be making very general or ‘casual’ requests like ‘play me music’ or ‘play me party music’, what comes out in response may be hyper-personalised to our tastes, using everything the music service knows about us.

This feeds in to my next point: These devices are a challenge for the music industry in terms of metadata. All of these new listening patterns — these voice queries and algorithmically-driven streams of music — are fuelled by metadata.

(No, that image above isn’t music metadata, as anyone with even a vague interest in programming will have already spotted! FAKE NEWS PICTURES…)

Is a song happy or sad? Indie or hip-hop? Is it good for cooking to or for working out? Is it from the 1960s, the 1990s or last year? Is it by this songwriter or that songwriter?

Some of this metadata has been provided by labels already to the digital services. Some of it has been provided but is wrong. And some of it hasn’t been provided at all, because we didn’t need it in the past.

Amazon has been pretty open about its willingness to create metadata that Alexa needs, if it doesn’t already exist. In fact, this is a task well suited to technology companies: they can use machine-learning to comb a catalogue of tracks and figure out what’s upbeat, what’s sad etc.

They can scan the lyrics and figure out which songs should be tagged ‘love’ or ‘wedding’ or ‘party’ or ‘songs about men not being hot’.

Spotify can scan billions of playlists created by its own users to figure out which songs are in people’s playlists for cooking or running or going to sleep.

So this is a challenge for labels: it’s been tough enough to provide correct metadata for who wrote a song, which publishers represent them and how the share was split.

But we’re now in a world where we may need to supply a lot more contextual metadata about the song itself, to ensure it gets served up by those algorithms. And if labels don’t create it, then it will be created for them.

But there’s also a positive, creative challenge ahead: Smart speakers are going to be really interesting for music marketing.

I have huge admiration for music marketers in the digital world. They’ve got to grips with building websites, launching mobile apps, running ad campaigns on Google and Facebook and umpteen other social platforms.

They know how to use smart links and retargeting pixels. They’re making chatbots and pitching to streaming playlists.

And now, the next task may be to figure out how to market in a voice-driven world. How do you promote your artist’s new track or new album to people listening to an Echo or a HomePod?

There’s no screen or display advertising, and if this is a subscription service, there won’t even be audio ads.

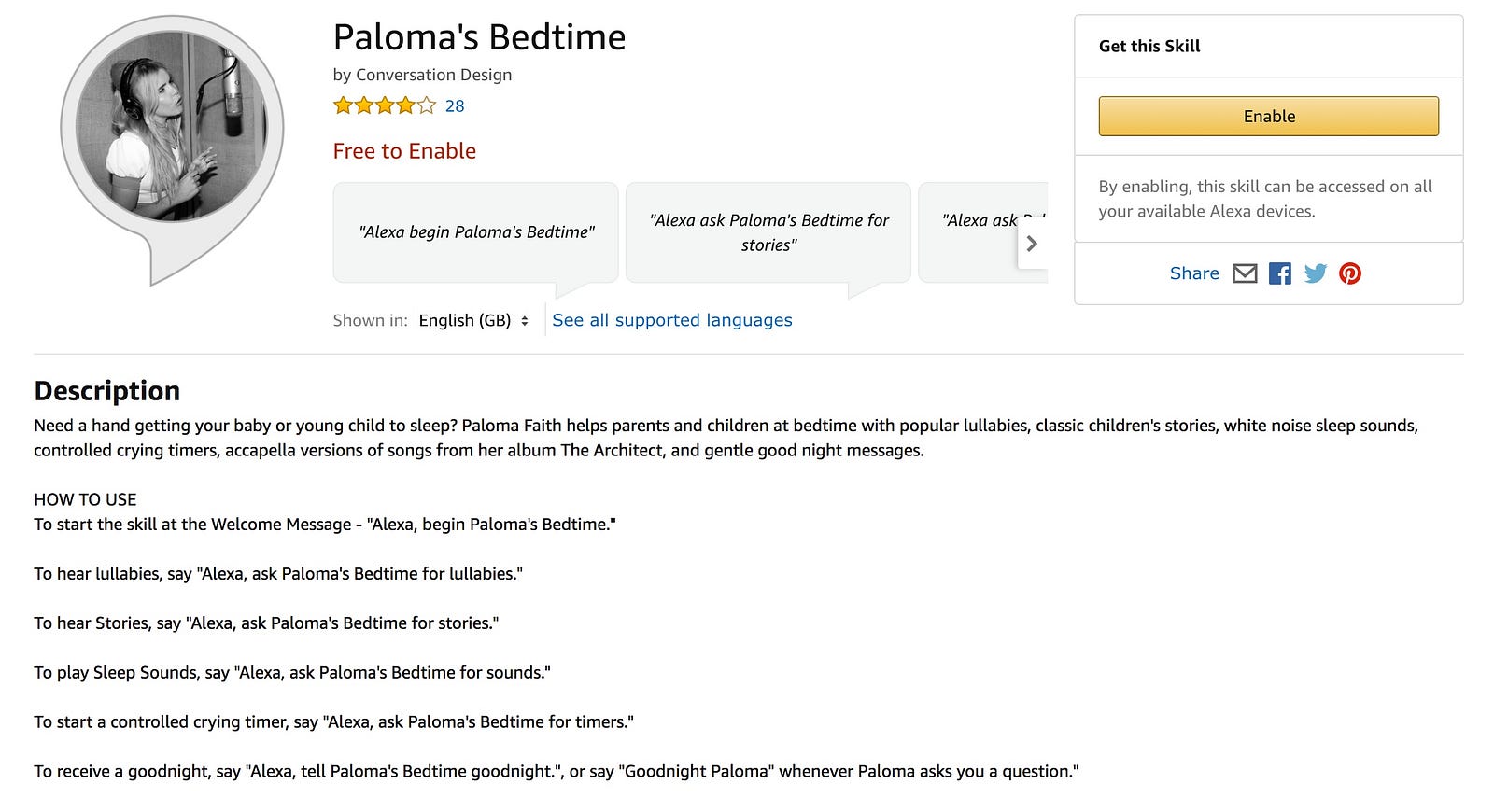

What there are are ‘skills’ for Alexa and ‘actions’ for Google Home, and hopefully in time something similar for HomePod. These are the smart speaker worlds’ equivalent of apps for a smartphone: applications built by developers and brands and music companies, which can be accessed through these devices.

Anyone can register and create an Alexa ‘skill’ — there are more than 15,000 already. There are skills for ordering an Uber or a Domino’s Pizza; for getting recipes read out as you cook; for guiding your seven-minute workout; checking your bank balance; and there are even audio-only games.

What there aren’t, yet, are many skills created by labels for artists, or even for catalogues of music.

Label RCA UK is a real pioneer here: they’ve launched an Alexa skill for Paloma Faith called Paloma’s Bedtime. It’s for parents with babies or young children: it’ll play lullabies, children’s stories, white-noise and acapella tracks from her latest album. It’s really interesting.

Much more can be done here. I also remember a conversation with a label executive who suggested that music discovery could be a conversation.

Your speaker says to you: “Would you like to learn about early jazz, the founders of hip-hop or explore music from Chicago?”.

You say ‘the founders of hip-hop’, and then Alexa or Siri tells you who Afrika Bambaataa and DJ Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash are; talks you through what they did and how they did it, and the culture around them in the Bronx in the 1970s — all while playing you the music.

The executive described it as “a discovery experience driven by dialogue… like when you talk to that great friend you have who knows about music”.

Nobody’s done this yet, but it could be an Alexa Skill or a Google Assistant Action. There could be a guide to ska; a guide to the New Wave of British Heavy Metal; a guide to grime. This is part podcast, part music playlist, but very much a conversation.

But equally, there could be a skill for Stormzy or Ed Sheeran talking you through their album. ‘Would you like to hear Galway Girl?’ I’ll let you decide your answer to that.

There is real potential here, not just for labels as marketing, but for artists as creative projects: what can they do with audio and interactivity?

The next talking point from our report: smart speakers are a challenge for pureplay streaming services like Spotify, Deezer, Pandora in the US. Companies whose main thing is being a music-streaming service, rather than that being part of a big technology company.

The three most prominent smart speaker brands in the west belong to Amazon, Google and Apple — who all have their own streaming services.

Amazon’s coolest voice commands: the ability to say to Alexa ‘play me music I last heard a week ago’ — work with its own services. You can’t even control Spotify or Deezer with your voice on a HomePod: it’s Apple-Music only, although you can use it as a Wi-Fi speaker to stream Spotify from your phone.

So, is it a problem for the pureplay services that this new route to listeners is controlled by their rivals? Spotify and Deezer are already lobbying here in Europe for regulators to make sure they get ‘fair access to platforms’ — we’ll hear that phrase quite a lot I think in 2018.

This isn’t a new problem: the same is true of smartphones and app stores — controlled by Apple and Google. But if labels are thinking about how the streaming market is going to grow, then it’s also important to think about control and power in that space, and how it’s being exerted.

I’m not painting the smart speaker owners as evil villains here. Amazon and Google both let you set Spotify as your default streaming source. Skills and Actions are one way those devices have opened up too.

My last point: smart speakers could have an impact on physical music sales.

This seems like a minor thing perhaps. The real focus here is whether these devices will boost streaming subscriptions. Yes, that may speed up the decline of CD sales more, but… It’s not the main thing.

But our research highlighted something else: these are not just music-playing devices. They’re shopping devices. Especially the Echo. By talking to these speakers, we’ll be able to buy tickets, merchandise, vinyl.

NPR and Edison Research found that 29% of smart speaker owners have used it to research something they might want to purchase, and 31% have added an item to a shopping cart to review later.

For now, this is pull rather than push — you initiate these transactions, but at some point, maybe it becomes more of a two-way conversation.

In the future, will Alexa say to me ‘Stuart, you love the Chemical Brothers’ — it knows that from my streaming history.

‘They’re playing Alexandra Palace in October, do you want a standing ticket?’ — it knows that I like to dance at a gig rather than sit down.

‘And do you want to pre-order their new album on vinyl?’ It knows I buy vinyl regularly.

There are lots of sensitivities around this: nobody wants their smart speaker to be battering them like an over-eager salesman. This week more than any other, thanks to the news stories about Cambridge Analytica and Facebook, a lot of us are thinking more deeply about who’s collecting data from us, and how that’s being used.

Still, the point about smart speakers is that these devices can be used to buy stuff, and musicians are selling stuff. So there’s something to explore here.

Read the full Everybody’s Talkin’ report on smart speakers and music here. It’s a 40-page PDF that’s free to download, and it’s a direct link: you don’t have to register any personal details first. The event writeup includes views from Amazon, Futuresource and music companies The Orchard, Kobalt, RCA and 7digital.