In this article Glenn Peoples explores the reasoning and process behind Pandora’s curation of the music they offer, and how it allows them to hand pick the best and most likely to be enjoyed tracks.

_____________________

Guest post by Glenn Peoples of Pandora on Medium

Key takeaways:

- Curation allows Pandora to surface the best of the over 50 million tracks available to streaming services. A mix of signals, data science and human analysis picks the best tracks to highlight for listeners.

- Recommending the best songs to listeners requires knowing the best versions of each track. The most desirable music should be highlighted and surfaced over duplicate tracks, poor recordings, re-recordings and sound-a-likes.

Today’s music fan has it good. Almost too good, in fact. Believe it or not, the amount of music available to consumers has grown 400-fold in fewer than 15 years. A large Tower Records store in a major city might have carried about 100,000 titles. Today’s online services boast over 50 million tracks — and steadily growing — that span genres, eras and continents. A couple decades ago, this enticing, almost wishful concept was called “a heavenly jukebox.” But at three-and-a-half minutes per song, it would take 320 years to listen to them all. Who has that much time? Sometimes just finding the right song seems like 320 years.

How does a service turn a wealth of music into a great listening experience? Pandora curates its catalog to focus on the tracks its listeners want most. Recommendations need to feel personal and intuitive. The listener should be able to ask, “How do they know me so well?”

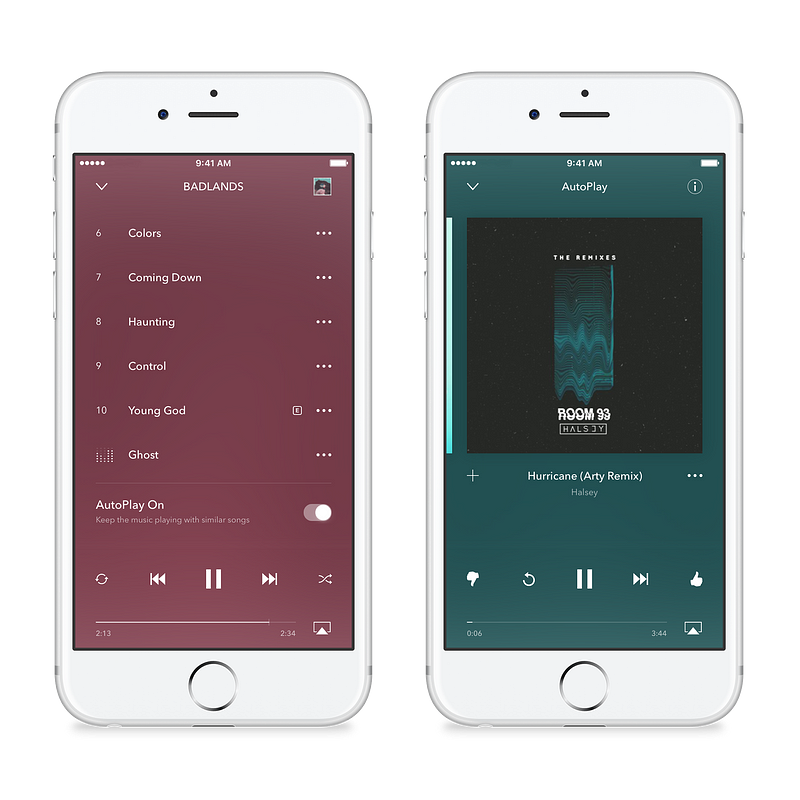

Thursday’s launch of auto-play on Pandora Premium underscores the importance of picking the right songs. Once a song, album or playlist has finished streaming, Pandora’s AutoPlay will start spinning songs similar the just-heard music, turning a lean forward, hands-on listening experience into a lean back radio station. While curation improves the lean forward experience — better browsing, better searching — it’s also crucial to lean back listening. After all, when listener has to press the skip button, the radio listener is leaning back a little less.

The very nature of digital distribution requires curation. In its early days, Pandora would rip songs from CDs in order to ingest and analyze them. It was like a radio station buying records to play on the air. This human-driven, manual process allowed Pandora to selectively build its catalog one song at a time from one CD at a time. Today, distribution is a digital firehose of single tracks, EPs, albums, box sets (the digital version, at least) and 99-song compilations of romantic jazz for rainy days.

All music streaming services have the same access to a universe of licensable recordings: decades of stars past and present, critics’ favorites, one-hit wonders, underground bands, legends within their genre, cult favorites and unknown, up-and-coming artists (plus soundtracks, movie scores and greatest hits collections). Pretty much everything. Available tracks include Enrico Caruso, theworld-famous opera singer who recorded in the first decades of the 1900s, all the way to Lil Yachty’s new album Teenage Emotions. More recordings are released every week—new music, remastered tracks and material converted to digital for the first time.

To handle the quantity of music, Pandora has an automated process for digitally ingesting music. This system constantly ingests tracks sent by distributors: new albums, singles, EPs, soundtracks and other compilations. Independent artists are always directly submitting tracks. But once the tracks are received, Pandora sifts through this sea of content with proprietary data science to find the music good enough to recommend to its listeners.

A variety of signals and resources guide Pandora’s efforts: labels known for releasing high-quality material curators believe listeners will enjoy; the reliability of other long-standing industry partners; plus coverage and commentary at editorial outlets. In addition, the Next Big Sound platform and data science team use signals from Wikipedia and all the major social sources as additional signals of artist’s growth and popularity to inform curation decisions. The team then analyzes the prioritized tracks using its proprietary data science, allowing Pandora to learn about their successful attributes and better assess future releases.

These efforts product tangible results. Curation, in its many facets, has consistently helped Pandora excel in recommendations — choosing the most appropriate songs to play, in other words — searching and browsing. This is vital: market research has consistently shown consumers rank recommendations and discovery among the most important features of a music streaming service. They want to find the music that best fits them, to hear familiar favorites and, from time to time, happily stumble upon — or so it would seem — unfamiliar artists. No unwieldy inventory of music can create that experience. Only by making the catalog manageable can a Pandora consistently bring the listener the right music.

Consider Leonard Cohen’s now-famous song “Hallelujah.” This one song has an original studio recording, multiple live versions and dozens of cover versions. Which song should be surfaced for listeners? The curator needs to determine which versions are worth highlighting. More often than not it’s the original studio version most people are most familiar with. But in the case of “Hallelujah,” Pandora surfaces the version from Cohen’s 2009 album Live in London rather than the original studio recording on 1984’s Various Positions. Numerous artists have covered “Hallelujah” over the years. Pandora also highlights version by Pentatonix, Rufus Wainright, Panic! At The Disco, k.d. lang, and the the John Cage cover that inspired the Jeff Buckley cover that helped turn the song into a classic.

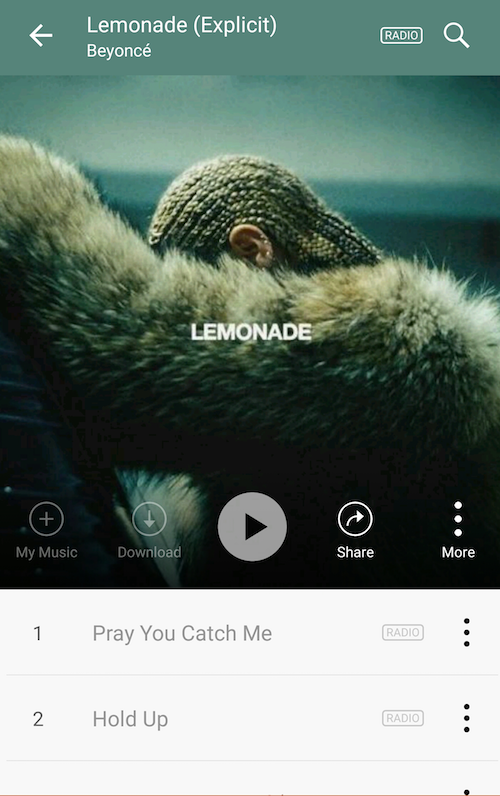

Curation has also given Pandora has content not found elsewhere. Since its days as a radio-only service, Pandora has catalogued rare B-sides, out-of-print tracks and music not available at competing services. For legal reasons — it was just radio, not an on-demand service — Pandora could stream any song by any artist. As a result, a parade of widely unavailable music has been heard on Pandora: Taylor Swift, Adele, Metallica, AC/DC, Garth Brooks, Jay Z, Beyonce, The Eagles, Bob Seger, Def Leppard, and Tool, to name the more popular names. Some of those artists are no longer digital holdouts. But because of a hybrid business model that layers Pandora Premium atop the original radio service, all of them have music available at Pandora

What’s more, curation improves the browsing and search experiences. Some songs, especially oldies, can be found on countless releases by the same label (multiple “greatest hits” collections, for example) and have been licensed for other compilations. Pandora listeners will usually hear the song from the best, most popular album. Take The Four Tops’ “I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch).” The original studio recording is currently available on at least 20 different collections — all released by the same label group! Pandora surfaces the album curators believe is the best, most important release that contains that track—in this case the Essential Collection.

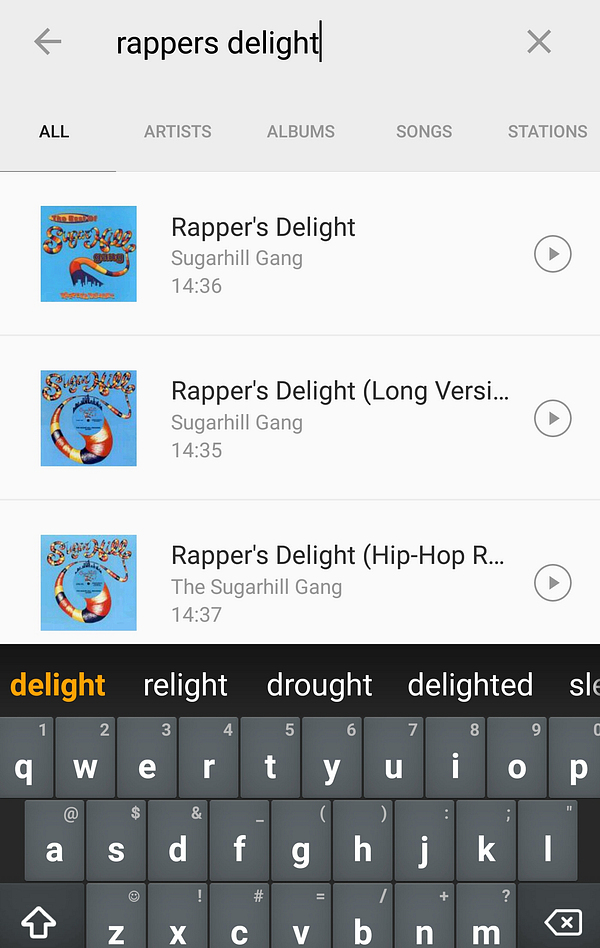

Another classic song suffers from an overload of versions. The original studio recording of Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” is available on a dozen or so different collections, not to mention the dozens more live versions and remixes. A Premium user doesn’t need so many options — especially since many are the exact same recording. Pandora focuses on three versions from the 1996 collection Rapper’s Delight: The Best of Sugarhill Gang. Easy.

The available 50 million tracks require a filter. Not all songs are the same. Not all recordings are the same.

Without curation, a listener is more likely to hear a re-recording of a favorite track or a recording with poor audio quality. Even small differences in quality make a difference. I think back to buying a copy of a Badfinger “greatest hits” CD only to discover the tracks — “Come and Get It,” “Baby Blue,” “No Matter What” and seven others — were actually re-recordings by original band member Joey Molland with other musicians. The classic recording of these songs can be found on albums released in the 70s by the Beatles’ label, Apple Records, and Elektra Records. Imitations are unflattering to these originals.

Without curation, a listener might hear a sound-a-like, a near-replica of a recording made by an unknown or anonymous artist. Digital distribution has allowed underground and unknown artists to reach digital services. But at the same time, digital distribution has also allowed sound-a-like recordings to flourish. Over the years intentionally fraudulent artists have recorded sound-a-like versions of popular tracks meant to confuse the listener. In addition, “music mills” have churned out have countless recordings that sound amazingly close to the original, popular recordings. An example is Kid Rock’s 2008 hit “All Summer Long,” an omnipresent song in the summer of 2008. “All Summer Long” reached #23 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in September 2008. But because Kid Rock was a digital holdout until October of that year, his original recording of “All Summer Long” wasn’t available at download stores. Sound-a-like cover versions were there, however, and Hit Masters’ version into iTunes’ top 10 tracks as a result. Some unassuming buyers found out too late and later showed their rage online.

Then there’s the positive, financial aspect of curation. Artists and labels benefit when Pandora highlights the preferred or primary version of tracks. More often than not, the best source for a song is the original studio album or a collection—greatest hits, boxed set—released by the artist’s label. But many popular and classic songs are often licensed to third parties who then release greatest hits compilations, soundtracks, and box sets. When a licensed track is spun, the royalty passes through the third party before being paid to the label. But when the original or preferred track is spun, the royalty goes straight to the record label (through its distributor) and gets to the artist faster.

The idea of a heavenly jukebox was promising in the ’90s. As author Charles C. Mann described it in a 2000 article for The Atlantic, this holiest of music services would hold “the contents of every record store in the world, all of it instantly accessible from any desktop.” (Apple would release the iPhone seven years later.) Mann’s estimation was hyperbole but struck at the heart of the problem: today’s premium service can feel overwhelming with 50 million tracks licensed by various distributors. Duplicates, sound-a-likes and miscellaneous debris scattered amidst millions of other tracks you’ll never want to hear…at that point a heavenly jukebox turns infernal. Heaven help us.