Although differences in song length didn’t have much of an impact on revenue when physical album sales dominated the industry, this is no longer the case in the age of streaming, suggesting that it’s time to revisit how the revenue pie is being divided up.

___________________________________

Guest post by Bas Grasmayer of MUSICxTECHxFUTURE

Is it fair that a 50-second song costs the same as a 20-minute composition? Back in the days of album-driven sales, track length didn’t matter much. If an album contains 50 tracks of 1 minute each (punk, grindcore), it would sell for roughly same price as an album with 3 tracks lasting 20 minutes each (post-rock, ambient).

Streaming services have changed this. Payouts occur on a per-stream basis. All songs treated equally. This means that if the amount paid per-stream is something like $0.005, Godspeed You! Black Emperor would make just 2 cents every time someone listens to Lift Your Skinny Fists Like Antennas to Heaven (runtime: 1h27m).

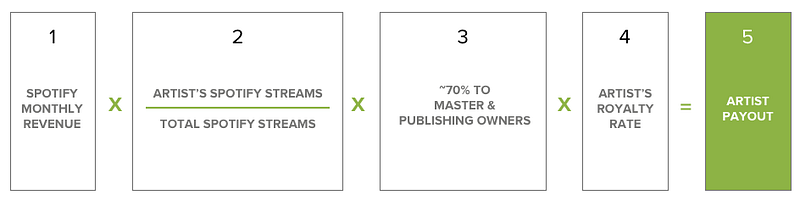

Royalty rates are variable and depend on total revenue vs total amount of plays. Spotify uses this formula:

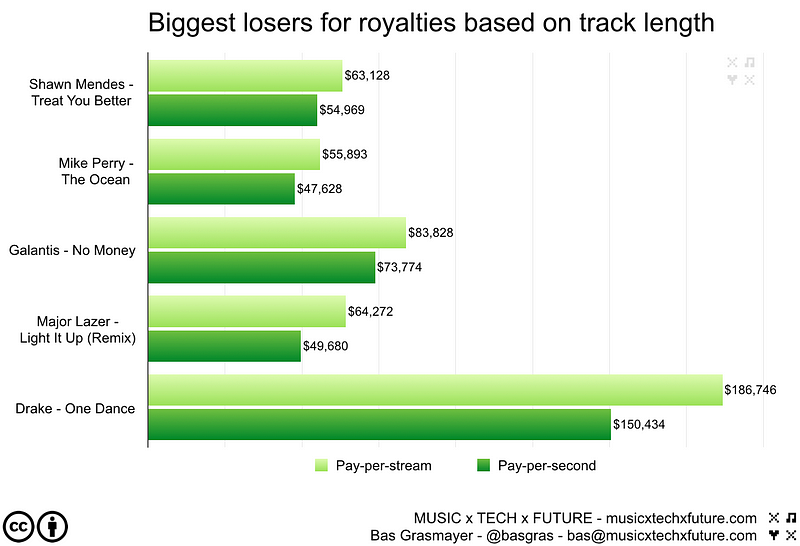

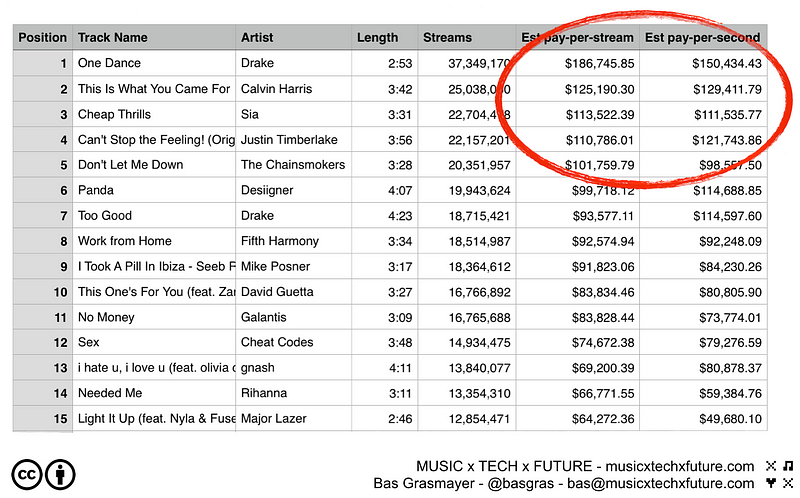

I took a look at Spotify’s top 50, since they publicly communicate the number of playbacks. Assuming a pay-per-stream rate of $0.005, which may differ from reality, I summed the total plays to understand the volume of the royalty pool and the cut each track would take. Then I took into account track lengths and compared the two. The difference for Spotify’s top hits runs into tens of thousands of dollars — per song.

If charts were based on time spent per song, rather than total number of plays per song, here are the biggest risers:

- Drake “Controlla” (24 → 15)

- Nick Jonas “Close” (32 → 23)

- G-Eazy “Me, Myself & I” (35 → 26)

And the biggest fallers:

- Mike Perry “The Ocean” (27 → 36)

- Shawn Mendes “Treat You Better” (16 → 25)

- Major Lazer “Light It Up (Remix)” (15 → 31)

Changes in accounting make a multi-million dollar difference

The top of Spotify’s global chart is not the most important area in terms of implications. The implications are greatest for artists and labels who produce music in genres that are structurally paid less per minute than other genres.

Spotify currently claims to have 100 million monthly active users. 30% of which are subscribers. They’re adding 1.8 million users per month. 80% of Spotify users use it multiple times a week, 25% use Spotify more than 20 days per month. It likely serves over a billion streams daily. Apple Music has 13 million paying subscribers. Other services hold millions more of users. All streaming hours and hours of music each month. According to the IFPI, streaming revenues amounted to $2.9 billion in 2015.

Massive pies are being built that need to be split fairly. Music industry analyst Mark Mulligan recently uncovered that indie music’s global market share is closer to 38% rather than the 20% conventionally believed and added:

“This matters not for bragging rights but because in the digital marketplace, market share shapes the deals that are struck, with more market share translating into better terms. So a more accurate measure of share can help the independent sector compete on fairer terms.”

Debates need to occur about market share, pay-per-stream versus time-based royalties, and the way subscription payments are divided. Streaming services are not the ultimate deciders in this: they’re locked into pay-per-stream royalties with the industry through contracts with differing renewal or extension cycles. Therefore, these changes need wide coalitions to occur. It would also help to have a truly competitive music streaming market that nurtures models beyond the typical $10/month all-you-can-eat services.

Streaming is here to stay. It’s a necessary layer for a healthy music landscape. In this landscape, it’s currently very difficult for artists to practice autonomy over the pricing of their music. Two $20 albums of equal length receive completely different payments for the same amount of plays if their track counts differ.

Is that fair?

Disclaimer: the royalty rate used in this article is based on an assumption and taken from a Billboard article dating back a year. In reality, royalties are slightly more complex eg. through subscribers’ streams counting heavier than ad-supported users’. Any total numbers resulting from using this assumption are therefore completely fictional.

However, even fictional numbers are useful in debating this. Whether the exact number per specific track is smaller or greater doesn’t matter. We’re still talking about how billions of dollars are distributed each year.

Hat tip to Cherie Hu for early feedback and sharing some data points.

Top image: Ocean of Sorrow, a work by Javad Alizadeh (CC/BY/SA).