In this article Shinjoo Cho delves deep into the success of the recent viral video of a Ukrainian accordionist playing ‘Summer’ from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, breaking down how the accordion functions and what makes the video so compelling.

_______________________________

Guest post by Shinjoo Cho on Soundfly‘s Flypaper

If you’ve spent any extended time scrolling social media this year, you’ve probably come across a video of Ukrainian musician Alexander Hrustevich playing “Summer” from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons (formally, the Violin Concerto in G Minor, Opus 8, No 2 “Summer”: III. Presto) on his bayan accordion. This footage of a spellbinding, virtuosic performance by a young soloist, has been viewed millions of times by people around the world, generating awe and eliciting so much impassioned reverence in the comments that it makes you stop and wonder how such a niche, exotic instrument could attract this many people. Is his playing truly noteworthy? Is there something unique about translating classical music to a traditionally folk instrument? Or is it something in the choice of piece specifically that makes the video special?

In fact, the video inspires a lot of inherent intrigue; and much of that has to do with what people don’t know about the world of accordion. To refresh your memory, here’s Hrustevich performing a section from Four Seasons.

How much do you really know about the accordion?

Let’s back up to get familiar with the accordion. The accordion was first patented in Vienna in 1829 by Cyrill Demian, but various instruments of its kind had been floating around Europe for at least a decade prior. Recently, there’s been a rising interest in the accordion among American performers across genres, including Tin Hat, Calexico, Counting Crows, and Gogol Bordello. However, in most pockets of popular culture, the accordion is still associated with nostalgic French waltzes, Argentinian tango and, sadly, uncool people. It is rarely presented in a classical concert setting.

Yet in countries outside the U.S., the accordion is omnipresent and taken seriously enough to be studied in music conservatories. China (whose mouth organ, sheng, dates back to 1100 BCE and inspired the development of some organ and accordion designs), North Korea, Russia and the nations of the former Soviet Union, Eastern and Western Europe, India, Latin America, the Caribbean, and even Canada all have musical traditions that feature the accordion and its cousins: the concertina, harmonium, and bandoneon. As a result of this wide ranging diaspora, the accordion has grown to include countless models, systems, and body styles.

The many reeds inside an accordion.

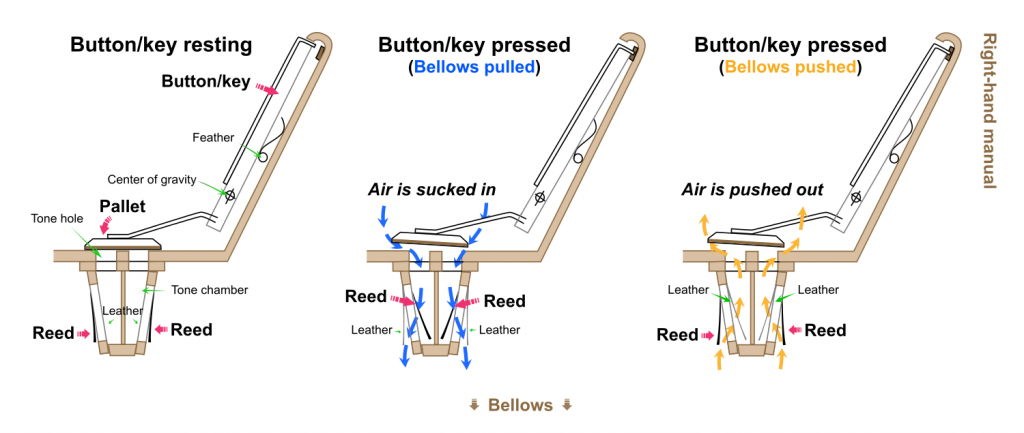

Accordions belong to the free-reed aerophone category of the reed instrument family. What differentiates free-reed instruments (accordion, concertina, harmonium, pump reed organ, bandoneon, etc.) from the rest of the reed family (such as the clarinet and saxophone) are their built-in reed systems. When the hand- or foot-operated bellows are pumped, air is pushed and sucked over the reeds. Most other wind instruments are operated by the human breath passing over the reeds.

An illustration of how the buttons work with the bellows to produce a tone through the system of reeds inside the accordion. Image via Wikipedia.

Some free-reed instruments, like the accordion, have multiple reeds per note, providing the many combinations of tone needed to recreate the timbres of the violin, oboe, musette, and clarinet among other sounds. These are selected by pressing the switch buttons, like these pictured below.

The design of the accordion is predominantly divided between piano and button styles, depending on the layout on the right hand side. The bayan, the Russian accordion played by Hrustevich, is a very advanced type of chromatic button accordion. The right hand section has five rows of small buttons laid out flat in a compact, slightly dizzying, zigzag chromatic pattern. This gives the player an impressive five-octave range, which allows them to play various intervals easily, and therefore, many styles of music, without having to switch to a different sound or revoice the melody.

Given that the piano accordion has a split-level keyboard capable of achieving only three octaves (the white keys are placed low and the black keys high), and a real piano has seven octaves, the five-octave bayan is in fact, more suitable for performing piano music than a piano accordion.

Made for the truly virtuosic musician, like Hrustevich, bayan accordions often feature a free-bass system. Most accordions use the Stradella bass system on the left hand side — two to six rows of buttons that play single notes and preset chords within a range of one octave, for easier playing. While this makes for a fantastic accompaniment vehicle, the left hand is not free to travel far, play different chords, or improvise like the right hand. A more modern invention, the free bass-system emancipates the left hand by assigning each button to only a single pitch, also in a zigzag chromatic pattern, that can span multiple octaves. This freedom comes at a cost — the left hand pattern is different from the right hand, so a player must learn and think in two distinct chromatic button layouts, not to mention that traditional playing posture also makes it difficult to see the left side of the instrument!

+ Read more on Flypaper: “10 Tips for Making Your Sheet Music More Readable”

What makes the music and the bayan so impressive together?

One of the most well known pieces of music in history, Four Seasons is a series of four violin concertos written in 1723 by Italian Baroque composer Antonio Vivaldi. It was originally written for solo violin, second violins, viola, cello, and basso continuo, and each concerto is a vivid portrayal of a distinct season and its happenings. The piece is composed in such a way as to allow for easy adaptation. The orchestration can be rearranged, depending on the size and make up of the ensemble.

The concerto form leaves ample room for improvisation and interplay between a soloist and an ensemble. This iconic work has been recorded over 1,000 times and reinterpreted in countless settings by composers of all genres in every instrumentation imaginable. Here’s just one:

So it’s not a stretch for an extraordinary player like Hrustevich to seize the orchestral and versatile nature of his instrument and build a career as an interpreter of the classical repertoire on his bayan. Out of all the seasons and the movements within,”Summer”: III. Presto was a wise choice. It allows him to show off the ability of the accordion to create thunderous, piercing voices depicting stormy summer weather, and to control his volume with every nudge of pressure on the bellows. At all times, he’s playing several lines simultaneously, all finely articulated and shaped, and faithful to the original version.

Reminder: These several melodic runs are moving in opposite directions on two distinctly patterned keyboards at a furious speed. Hrustevich is actually playing this movement a few BPMs faster than a traditional orchestra would!

This is all while maintaining superb control of the bellows on the left hand, which is the heart and lungs of the bayan’s sound. The bellows are analogous to the bow of a string instrument and the a breath of a singer. The up bow and down bow have distinctive characteristics and roles. The singer must prepare adequate air so the voice doesn’t just deflate, or stop, in the middle of a phrase. The bellows are responsible for the tone, articulation, dynamics, and phrasing.

The Zonta ZB16 bayan accordion.

To obtain mastery like Hrustevich’s requires full body coordination and mastery of air movement in order to play so seamlessly and with nuance. When he shakes the bellows (fast, repeated opening and closing), he’s imitating the tremolo of the strings with high precision and incredible control of the air supply. And often, all his fingers are deployed, moving furiously over 200+ identical buttons without looking, all while the instrument itself is constantly moving to push air through the reeds. It’s akin to dancing on a moving vehicle, while driving the vehicle… blindfolded.

+ From the archive: “The Global Fiddle — A Love Letter To The Violin”

So why do we feel what we feel?

Yes, the accordion sounds kind of goofy, and yes it is steeped in folk tradition more than classical. But, as is clear in the video, accordion playing is very physical. The audience gets a full frontal view of what’s happening on two columns of buttons and bellows in constant motion. For the player, the physical nature of being strapped into what is essentially a full organ, whether it’s accompanying a singer’s soulful melody or to imitate a orchestra’s leaps and bounds, is a big part of the thrill. Add to this a dazzling display of a baroque chamber ensemble being imitated on a single instrument and it’s bound to fascinate.

It’s not only the performance, but the exoticism of foreign mastery that allures us as well.

In my travels studying the accordion and bandoneon (in Serbia, Argentina, and the U.S.), I have found that when the accordion comes up, people often mention elder members of their family who used to play, the presence of idle dusty accordions in their attic, or how they used to take accordion lessons until they opted for a more stylish instrument. This just shows the local, folk-traditional ubiquity of the instrument until around the mid-20th century.

With the advent of popular music that had no room for accordion, and the lack of a “classical” repertoire to offer it any kind of safety net, the accordion was basically set adrift. Outside of the American folk traditions such as bluegrass, Cajun music, Irish jigs, and klezmer, the instrument became less visible. All of this has likely made the sight of a virtuoso accordionist today so exciting. To see the accordion reincarnated in such a way, and lifted up to produce this immediate an emotional reaction in people, makes me ponder what remains to be discovered with other instruments and genres whose popularity has faded.

If Hrustevich has you interested in learning more about noteworthy free-reed instrumentalists, here’s a list of some artists you should know about:

Pauline Oliveros (US)

Ludovic Beier (France)

Sandra Milosevic (Serbia)

Lidia María Hernández López (Dominican Republic)

Geir Draugsvoll (Denmark)

Buckwheat Zydeco (US)

Leopoldo Federico (Argentina)

Pandit Kishore Banerjee (India)

Lidia Kaminska (Poland/US)

Richard Galliano (France)

Nini Flores (Argentina)

Nikolay Sivchuk and Alexey Peresidly (Russia)

Aniceto Molina (Colombia)